With a predominantly youthful population and an emerging socio-economic development momentum in Africa, Nigeria has a significant opportunity to secure a prominent role in global emergence in the forthcoming decades. However, the realization of this potential hinges on the effective development and deployment of human capital capable of steering the nation’s progress. Given its role as the primary source of human capital in Nigeria, the education sector assumes heightened importance in the coming decades. Unfortunately, this sector has been besieged by numerous challenges, resulting in gaps that compromise the nation’s human capital. These challenges can be broadly categorized into three groups:

- The Access Gap

- The Quality Gap

- The Outcome Gap

A comprehensive examination of the access gap, encompassing challenges hindering the average Nigerian’s access to education, has been outlined in the provided document HERE.

Additionally, the quality gap, addressing the challenges that undermine the capacity of available education to adequately equip individuals, has been analyzed HERE. The outcome gap delves into the human capital implications arising from both limited access and low-quality education. This policy brief focuses specifically on the outcome gap, offering insights into its realities, ongoing solutions, and identified gaps. Furthermore, the brief presents policy recommendations aimed at bridging the gap and fostering positive outcomes in education.

Understanding the Outcome Gap

The outcome gap can be understood in 5 related challenges:

- Education Transition Challenge

The Nigerian education system operates on a hierarchical structure, where progression between education levels is not automatic. Learners can advance to the next stage only upon demonstrating mastery outcomes, typically through standardized examinations. For instance, primary school students must pass entrance exams to qualify for secondary school, and tertiary institutions require a minimum number of WAEC* subject passes and UTME* scores for admission.

Poor outcomes at any educational level pose an additional hurdle to accessing higher education. Between 2016 and 2023, the percentage of students meeting the minimum 5- subject WAEC pass, a prerequisite for university admission, ranged from 53% to 79.8%. Consequently, at least one in every four high school students during this period was denied the opportunity to transition to higher education solely based on subpar outcomes, aggravating the challenges of education access and contributing to the leaky education pipeline—the progressive reduction in access to education as one ascends the tiers of education. Current strategies to address this transition challenge include a deliberate reduction of barriers between educational tiers. For instance, the Joint Admission and Matriculation Board (JAMB) has incrementally lowered the minimum UTME score required for university admission, from 180 in the 2009 admission cycle to 140 in the 2023 admission cycle. However, this has prompted public outcry, with education experts cautioning that continued reductions may compromise academic performance in tertiary institutions.

- Education and Industry Disconnect

A major public critic of tertiary education particularly is its disconnect from the industry. Although the academia is expected to play the role of both a human capital supplier and a research-based innovation kickstarter for industries, this has not being the much of the case of Nigerian tertiary education. Students in higher education have limited exposure to the industry, and tertiary education curriculum places a major focus on academic content over helping students develop employable skills. The lack of research financing has also made it difficult for higher education institutions to lead the innovation trail as expected. To address the disconnect, various stakeholders at several levels have being implementing diverse solutions. The Federal Government instituted the Student Industrial Work Experience Scheme in 1974 through the Industrial Training Fund (ITF). SIWES was created to bridge the gap between the classroom and the industry by preparing students with the appropriate skills necessary for employment in Nigerian industries. The scheme however mostly caters to students within the STEM disciplines, with some inclusion of Agriculture, Medical Sciences and Education students. There has also been criticism of the effectiveness of the scheme based on the short duration, inability to transition to actual employment, poor matching of student placements, insufficient participating industries, and insufficient funding.

On a relatively local scale, some universities have created special strategies to connect the classroom with the industry. An example, the Vice Chancellor of University of Abuja as at August 2023 reports the university’s attempt to bridge the academia-industry disconnect through special strategies like creating industry-supported programmes within the University. The VC also reported the university’s plan to create an academic head of department and an industry head of department for its department of Mining and Geology as another example of actively involving the industry in the academic environment.

- Employment Challenge

Education holds two significant promises: social mobility, enabling individuals to enhance their socioeconomic status, and social efficiency, furnishing the necessary human capital to contribute to societal development. However, the current state of education in Nigeria poses increasing challenges to realizing these promises. The adverse employment outcomes resulting from limited access and low-quality education manifest in three ways: unemployment, underemployment, and unemployability. Unemployment denotes a complete lack of suitable job opportunities for individuals willing and able to work, while underemployment involves occupying positions that underutilize employees’ skills and compensate them inadequately. Unemployability, on the other hand, describes situations where a person is deemed unsuitable for employment and unable to retain a job, often stemming from a mismatch between the skills possessed by an educated individual and those required for the sought-after positions (Obor and Kayode, 2021).

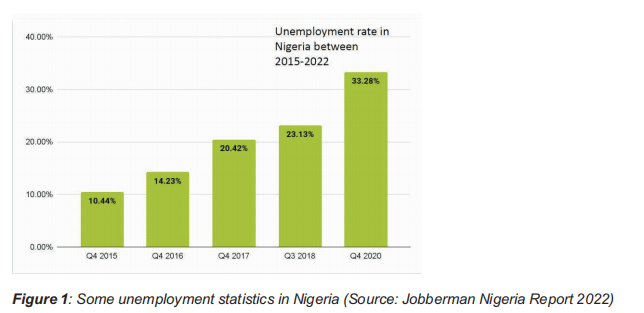

Unemployment poses a significant and enduring challenge in Nigeria, primarily driven by a scarcity of job opportunities and exacerbated by global factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the past decade, the unemployment rate has seen a steady increase. In the fourth quarter of 2020, it reached 33.3%. However, in the first quarter of 2023, the Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS) revised its methodology for calculating the unemployment rate, publishing a revised figure of 4.1%. The updated system now considers employed persons as those in paid jobs who worked for at least one hour per week, a departure from the previous threshold of 20 hours per week. Despite the NBS asserting alignment with the International Labour Organization (ILO) guidelines, this revision has faced criticism from the Nigerian public. The NBS had previously reported an underemployment rate of 20.1% in Q3 2018 and 13.7% in Q4 2022. Under the revised system, the NBS now defines underemployment as a proportion of employed individuals working fewer than 40 hours per week, declaring themselves willing and available for more work, with a updated rate of 12.2% in Q1 2023.

Notably, there is a lack of comprehensive nationwide measures for unemployability in Nigeria. Its impact is observed in the paradoxical combination of unemployed graduates alongside reported shortages of skilled human resources by employers in the country. This situation has prompted a noticeable trend of labor recruitment from other countries by Nigerian-based companies, exemplified by the employment of 11,000 Indians in the newly constructed Dangote refinery, partially funded by the NNPC. The ensuing controversy has triggered a public debate on the unemployability challenge in Nigeria.

The relationship between the state of education in Nigeria and its impact on youth employment and employability can be understood from a dual perspective. On one side, a lack of access to basic education impedes the development of the intellectual capacity required for employment within the globalized economy. Conversely, on the other side, low-quality education results in graduates struggling in the workplace, restricting them to positions that impede their social mobility. Both scenarios lead to a similar challenge: young individuals find themselves unable to contribute optimally to the socio-economic development of the nation. Global challenges, which have led to economic contractions, add another layer to the issue by limiting job opportunities. This exacerbates employment challenges, making it difficult even for well-educated graduates to secure well-paying jobs. In essence, the intersection of restricted educational access and substandard quality compounds the hurdles faced by young people in making meaningful contributions to the nation’s socio-economic progress.

- Job Creation Challenge

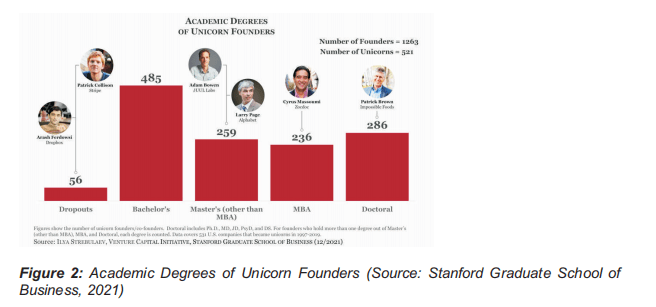

The impact of low-quality education extends beyond limiting job prospects for graduates; it also diminishes the likelihood of job creation in the first place. Research indicates a correlation between increased opportunities for job creation in an economy and increased opportunities for intellectual sophistication that equips individuals with the necessary worldview and technical skills for entrepreneurial exploration. A 2021 study conducted at the Stanford Graduate School of Business revealed that over 95% of 1263 Unicorn Founders globally held at least a Bachelor’s Degree, with over 60% of them possessing a graduate degree (Figure

2). Notably, all seven unicorn founders in Africa as of 2022 held higher education degrees. In essence, businesses generate jobs, and individuals with a strong educational background are more likely to establish successful businesses, contributing to job creation.

The impact of the current state of education on the younger generation extends beyond socio-economic aspects; it also has emotional implications. There is a noticeable decrease in the socio-affective engagement with education among young people when compared to earlier generations. What is particularly alarming is that this decline is not confined to those with limited access to education at the basic level or those affected by the leaky pipeline phenomenon, which reduces the percentage of individuals able to pursue higher education.

This trend is also evident among individuals currently within the educational systems. Research indicates a growing disinterest in education and a diminishing belief in its promises among the youth. Young people are becoming increasingly disconnected from the aspirations and assurances that education is supposed to offer.

Apart from academic research, this waning interest is also evident in various sociocultural shifts within Nigerian social spheres. These shifts reflect trends and discussions that indicate a noticeable departure from the once prevalent notion that obtaining an education serves as a pathway to social mobility and efficiency. Over the past decade, the surging popularity of the ideology “School Na Scam” (Translation: Schooling is Fraud) has sparked public controversy, leading to a significant increase in debates about the relevance of education, particularly higher education, to the socio-economic outcomes of contemporary youth. This ideology has gained widespread popularity, as evidenced by its inclusion in popular and widely-accepted creative works, such as songs by purportedly successful young individuals who assert that their achievements are not attributable to their educational experiences.

Although closely connected to the socio-economic outcome, the affective outcome differs in that it is more internalized, shaping internal perspective and eventually, external culture. Scholars argued tht societal perception and values are pivotal to the development of the culture of education(Famoye, 2021). Left unaddressed, the declining affective outcome has the capacity of reshaping an entire’s generation disposition towards education, impede educational progress, and reverse the advancements made in education in the decades to come.

Policy Recommendations

- Better Measurement of Educational Outcomes in Nigeria

There is a striking absence of effective nationwide measurement of education outcomes in Nigeria. This deficiency in quality data hinders a comprehensive understanding of education outcomes at various educational levels and the intricate relationships among them. Furthermore, it undermines the capacity to gauge the effectiveness of interventions and increases the likelihood of continuously reinventing solutions that may not be yielding optimal results.

Moreover, most of the existing measurements of outcomes, particularly at the primary and secondary school levels, are predominantly quantitative, placing a strong emphasis on grades. There is a compelling need to adopt a multidimensional approach to measuring outcomes, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative assessments while building an understanding that spans both short-term and long-term perspectives. Developed nations, for example, the United States, capture a more robust and well-rounded comprehension of education outcomes by employing a combination of quantitative and qualitative measurements. They also embrace a longitudinal view when assessing outcomes. A notable example is the 2012 Education Longitudinal Study (ELS), which offers trend data about critical transitions experienced by students as they progress through high school and transition into post secondary education or their careers. Recognizing that the impact of education extends beyond the short term, a longitudinal approach aids in capturing the multidimensional, long-term effects of education, providing a more realistic picture of educational outcomes.

- Stronger Academia-Industry Relationship

Establishing a more robust connection between academia and industry is imperative to strengthen the socio-economic outcomes of education. Particularly in higher education, students need exposure to the real-world challenges within society that their education aims to equip them to address. Ossai (2023) proposes two models to help students translate abstract concepts learned in the classroom into real-world contexts. The first model advocates for the creation of discipline-based incubation spaces. In STEM-focused disciplines, these spaces can serve as Innovation Centers where students apply STEM principles to solve local challenges. For non-STEM fields such as arts, social sciences, and law, these incubation spaces can function as Thinking Clinics. Here, students engage with real-world case scenarios that require application of their field’s knowledge beyond rote memorization. The second model advocates introducing Experiential Capstone Projects to replace the current abstract and theoretical undergraduate thesis model. Experiential Capstone Projects would task students with designing solutions to problems within their local communities, serving as the culmination of their higher education journey. These models leverage established practices within higher education and have already been successfully implemented by universities in Africa, exemplified by the African Leadership University in Rwanda. This demonstrates the viability of such approaches even within the complex African context.

- Promoting the Civic Responsibility of Education

Public discourse on anticipated outcomes of education should not only emphasize socioeconomic returns but must also encompass civic responsibilities. Graduates should recognize that education equips them not solely for employment and social mobility but also to fulfill their role as responsible citizens of the nation. Framing educational outcomes exclusively in economic terms risks stripping education of it’s responsibility to nurture individuals who comprehend their role in active contribution to social cohesion. A predominant emphasis on the socioeconomic returns of education contributes to a decline in the socio-affective disposition, particularly among youths, towards education, given the challenges of an increasingly complex global economy. Broadening the portrayal of education beyond economic returns can shift the narrative from viewing education merely as a means to secure a job to understanding it as a tool that empowers learners to address and solve societal problems. This holistic perspective encourages graduates to recognize their civic duties and promotes a more comprehensive understanding of the transformative potential of education in fostering responsible and engaged citizens.

*WAEC: West African Examination Council

*UTME: Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination

References

- Famoye, A.D. (2021). The Implication of Societal Perception and Value on Quality Education: The Nigeria Example, 1999–2019. In: Mojekwu, J.N., Thwala, W., Aigbavboa, C., Atepor, L., Sackey, S. (eds) Sustainable Education and Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68836-3_1

- Odu Obor, D., Kayode, D.I. (2022). Highly Educated but Unemployable. In: Baikady, R., Sajid, S., Przeperski, J., Nadesan, V., Rezaul, I., Gao, J. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Problems. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68127-2_162-1

- Ossai, Edem (2023, September 20) Redefining the Role of Tertiary Educator in Nigeria [Webinar]. The Education Partnership Webinar Series. www.youtube.com/watch?v=rsJjvzOw8Q4