The state of Nigerian education is faced with myriad challenges. In 2023, UNICEF reported that 75% of children aged 7-14 lack basic literacy and number skills. The World Economic Forum ranked Nigeria’s quality of primary education at 120th and its quality of tertiary education at 117th out of 137 countries in 2017/2018.

For a nation whose population is one of her greatest strengths, with youth majority, education becomes even more pertinent. The challenges of education can be grouped into 3 major gaps:

- The Access Gap

- The Quality Gap

- The Outcome Gap

The Access Gap groups the challenges limiting the Nigerian populace’s access to appropriate education. It includes issues of out-of-school children, low completion rates, low percentage of transitions between education tiers, adult illiteracy, education in emergencies, etc. The Quality Gap encompasses challenges that result in inadequate equipping capacity of the available education. The Outcome Gap covers the human capital implications of the low skills that result from low-quality education. A detailed analysis of the Access Gap is provided HERE. This policy brief zooms into the quality gap, providing insights into its realities, current solutions, and existing gaps. Some policy recommendations to help bridge the gap are also discussed.

Understanding the Quality Gap

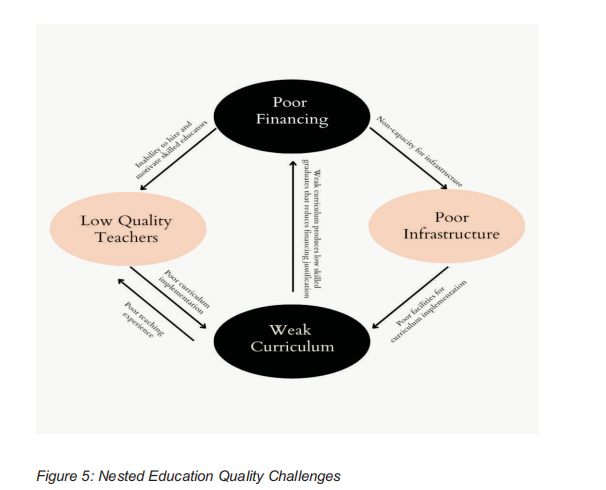

The problem of low-quality education is fuelled by 4 key interrelated issues:

- Weak Curriculum

Curriculum is a critical input of education. Its development, design, content, and implementation have a significant impact on the quality of education. At all school levels, education in Nigeria is buffeted by a weak, outdated, and overloaded curriculum that is fighting for relevance in the context of the country’s needs.

On the development and design end, there is the challenge of using a top-down approach, with teachers having little to no contribution to the development of the curriculum. Also, there is inadequate qualitative research that focuses on understanding the cultural and psychosocial dynamics of the student in a way that can enrich the perspectives used in developing the curriculum. On the content end, there is an outdated, overloaded, and inflexible structure of curriculum content at the different tiers of education. On the implementation side, there is the nested problem of weak management that is disconnected from teacher’s instructional realities and the low capacity of teachers to implement curriculum.

The weak curriculum challenge mutates at different tiers of education. At the primary and secondary levels, the proliferation of unregulated private schools has particularly weakened the curriculum. Whereas at the tertiary level, the curriculum is mostly theoretical with little practical input that can help students connect their learning to the realities of their daily personal and community needs.

Tertiary education curriculum also suffers under the weight of imperialism and a disconnect from indigenous knowledge in various fields, which in the long term produces disenfranchised learners who always have to navigate a double, almost mutually exclusive, school life and home life. Researchers have shown that this disenfranchisement has far-reaching impacts not only on the intellectual capacity of the Nigerian learner but also on their confidence as solution creators. Ezeanya-Esiobu (2019) reported that:

“Several decades after the end of colonialism, sub-Saharan Africa has not made much progress in liberating the education process from the clutches of imperialism and dependency.

Only marginal improvements have been recorded, such as an increased rate of enrollment, expanded infrastructure, training, and recruitment of more teachers, and other improvements that are peripheral to the core issue of curriculum transformation. African pupils and students graduate from different levels of education, with a sense of helplessness, inferiority, and deference to Europe. In other words, the more the African studies, the deeper his inability to utilize his knowledge to directly and progressively influence his immediate environment for the better.”

Several solutions have been proposed for addressing the curriculum challenge. Efforts are continuously being made by the Federal Ministry of Education towards revising the curriculum at the primary and secondary school levels. However, this has been generally slow and focused on single disciplines; for example, Civic Education was reviewed within the Secondary School curriculum in 2017 and History was reintroduced into Basic education in 2022. In an effort to thrust university education towards global standards and reflect 21st-century realities, the National University Commission in 2022 approved a new curriculum dubbed the Core Curriculum and Minimum Academic Standards (CCMAS). CCMAS is the result of a comprehensive review of Benchmark Minimum Academic Standards (BMAS). It is aimed at providing 70% of university education content and expected outcomes, while Universities provide 30% based on their contextual peculiarities. However, the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) kicked against CCMAS, stating that it was created using a top-to-bottom model that did not fully carry the university educators along in its development. There remains an existing challenge with the curriculum of education in Nigeria.

- Teacher and Teaching Issues

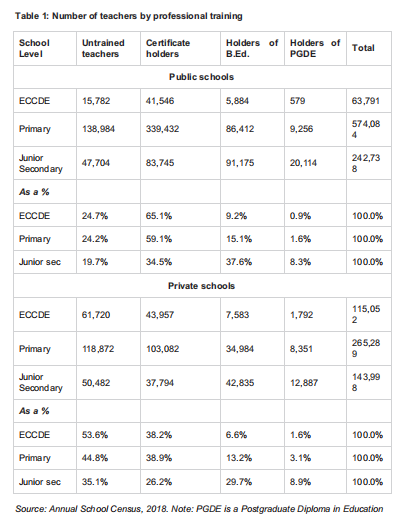

Quality education is impossible without quality and qualified teachers. As the major human capital in the mix of factors of education, teachers hold a crucial role in the work of ensuring quality education in Nigeria. 4 major challenges make teaching and teachers contribute to the quality gap. First is the Inadequate Qualification challenge. The Education Sector Analysis carried out in 2022 by the Federal Government in partnership with The World Bank and UNESCO revealed that at least 20% of the teachers in public basic education schools are not qualified to teach. This number nearly doubles in private schools. (Table 1)

The problem of low qualification is worst at the Early Childhood Care Development and Education (ECCDE) tier, as only 1 in every 10 public ECCDE teachers holds a Bachelor’s or Postgraduate Diploma in Education. At the primary level, the majority of the teachers in public schools (60%) hold a National Certificate of Education (NCE), while only 15% have a Bachelor’s Degree in Education. The situation deteriorates in private schools, where over 4 of 10 teachers lack NCE. Although the official requirement for teaching at the secondary school level is a Bachelor’s Degree, one-third of teachers in public junior high schools hold only an NCE, and about 20% do not have any professional qualifications

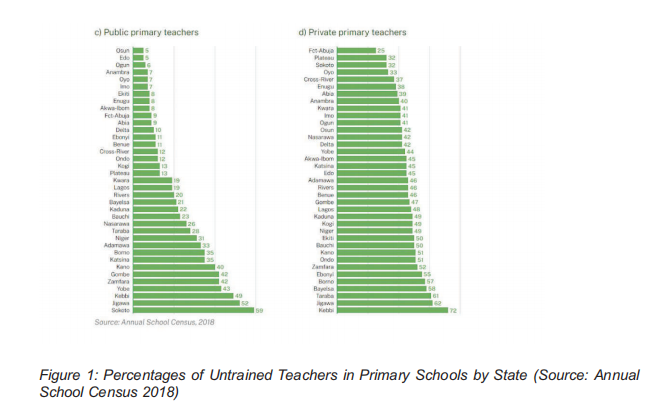

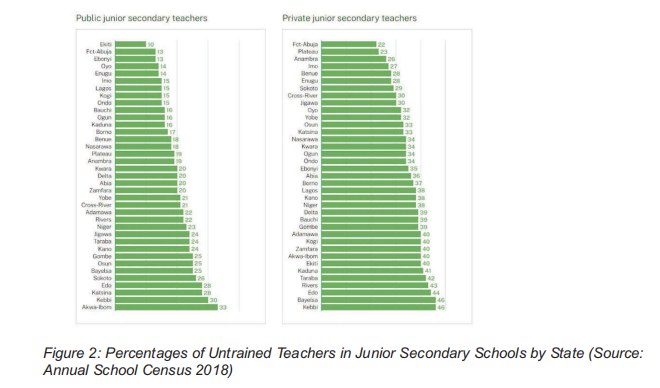

The number of completely untrained teachers rises to 35% in private junior schools, with another one-fourth holding only NCE. It is important to note that this problem of unqualified teachers is unevenly distributed in the country, as reported by the 2021 Education Sector Analysis. For instance, in public primary schools, the proportion of untrained teachers ranges from 5% in Osun to 59% in Sokoto. In private schools, it ranges from 25% in the FCT to 72% in Kebbi (Figure 1). In public junior secondary schools, the share ranges from 10% in Ekiti to 33% in Akwa-Ibom, while in private schools, it ranges from 22% in FCT-Abuja to 46% in Kebbi

(Figure 2)

“all teachers in tertiary institutions shall be required to undergo training in the methods and techniques of teaching”, there is no evidence that tertiary educators undergo any form of education training or is mandated to do so.

The second issue builds on the first. Aside from the lack of pre-service training, teachers also lack in-service professional development opportunities. The 2022 National Personnel Audit conducted by the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) revealed that 67.5% of teachers in public schools and 85.3% in private schools have not attended any in-service training in five years. Although the Revised National Policy on Education (2013) speaks of the provision of educational support services, including local government-based Teacher Resource Centres that can provide professional development space for basic education teachers, there is no evidence that this has been implemented a decade since the policy revision. At the tertiary level, although research has confirmed the importance of centres of teaching and learning support within Universities, Ajilore (2021) reported that less than 5% of universities have such centres, and the available ones are rarely concerned with educators’ instructional practices.

The third issue details the global crisis of teacher shortages. Recent data from UNESCO showed that sub-Saharan Africa needs to recruit 16.5 million more teachers to reach its education goals by 2030. In 2018, the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) reported shortages of teachers at the basic education level up to 277,537. The Revised National Policy on Education (2013) prescribes a student-teacher ratio of 1:25 for pre-primary classes; 1:35 for primary and 1:40 for secondary schools. However, in February 2023, UNICEF placed the average pupil-teacher ratio across the three states in NorthWestern Nigeria as high as 124:1 as a result of the insurgency.

The fourth issue is the low perception of the teaching profession, which is based on a mix of poor remuneration and poor work conditions. Ikiyei & Enekeme (2023) studied the perception of the teaching profession among 300 third-year undergraduate students in the Faculty of Education at a Nigerian University and found 3 of 4 of these future teachers did not willingly choose the education path. They only accepted to study an education-themed course just to get a tertiary degree. 72% of them agreed that they were ashamed to introduce themselves as future teachers. The teaching profession has suffered progressively lower perceptions with increasingly challenging challenges such as low and unpaid salaries; lack of provision of professional development; career inflexibility, and more. Salaries for primary school teachers within public institutions can go as low as less than $80 monthly. And there have been records of teachers being owed salaries for up to 8 months in some Nigerian states. At the tertiary level, a full professor earns less than $600 monthly in Nigeria as against over $5,000 in South Africa. This has made the profession unattractive to young, bright minds who can bring modern innovation.

Although the issues surrounding teaching in Nigeria posit a strong quality challenge, there have been efforts to address them. Some of these efforts include stricter regulatory practices to ensure teachers are qualified. For example, in December 2019, following the 62nd National Council Education Meeting directive, the Teachers’ Registration Council of Nigeria was saddled with the work of removing all unqualified teachers from Nigerian classrooms.

However, in a typical case of a lack of goodwill for policy implementation, some state governments disregarded the directive. In 2016, the Federal Government announced that it would employ 500,000 new graduates and NCE teachers in the basic education sub-sector.

There has not been much news detailing the implementation of this plan. UBEC reported that the federal government disbursed over N57 billion to assist states with the Teachers Professional Development (TPD) programme between 2009 and 2022. In 2022, the federal government announced digital literacy training for 45,000 teachers across 24 states including Benue, Bauchi, Ebonyi, Enugu, Gombe, Ekiti, Lagos, Osun, and Jigawa. There, however, remains a lot more to do to ensure qualified teachers who are able to provide quality education.

- Infrastructure

Education Infrastructure is the element within the learning environments that make learning accessible and easy. They include classrooms, laboratories, learning tools, pieces of equipment, school facilities, etc. Evidence exists that high-quality infrastructure facilitates better educational quality and outcomes. The state of educational infrastructure in Nigeria is dire. From overcrowded classrooms to dilapidated buildings, inadequate books, and more; infrastructural neglect is a common challenge of the various tiers of education in Nigeria. At the primary level, there are reports of students having to sit on bare floors to learn (Figure 3).

At the secondary level, there are cases where students are unable to learn because of flooding inside the classroom. Infrastructural challenges at the tertiary level not only impede education for learners but also make cutting-edge research unreachable for professors. The leading causes of infrastructural challenges include lack of political will, low financing, corruption, project abandonment, poor maintenance culture, and poor planning.

There have been reports of interventions being carried out at the various levels of government to address this infrastructure challenge. In 2022, the Federal Government of Nigeria was reported to have spent over N6.3 trillion on capital projects in education, particularly on the development of ICT and other infrastructure since 2015. A total of N553 Billion of this amount was reported to be expended on the development of infrastructure at primary and secondary levels of education. This was allocated to the construction, renovation, and rehabilitation of classrooms, hostels, and laboratories as well as security infrastructure.

- Inadequate Financing

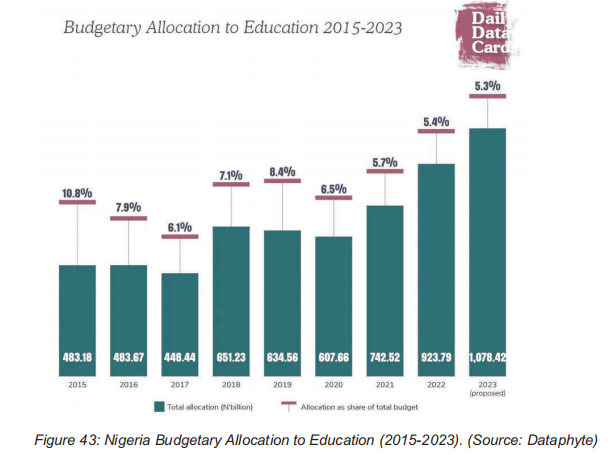

UNESCO recommended that developing countries allocate 10-15% of their budgets to the education sector. In 2015, education was allocated 10.8% of the Nigerian budget. Since then, the allocation has progressively tanked to 5.3% in 2023 with a few peak periods in 2018 and 2019 (Figure 4). Education Financing in Nigeria mostly rests upon the government and is distributed across the 3 tiers. Basic education is financed through a concurrent financing mode from the 3 tiers of government—federal, state, and local government authority, with distinct financing mandates and responsibilities for each tier. The federal government provides 50% and the state and local government 30% and 20% respectively.

With rising debts, global instabilities, and shrinking economies, education in Nigeria is at risk of heightened under-financing which can exacerbate every other challenge associated with the quality gap as well as the challenges associated with the access gap, especially with increasing costs intensified by the destruction of educational infrastructure by insurgent attacks.

Efforts are being made at all government levels to ensure proper financing of education. In 2019, the new administration of the Oyo State Government upwardly reviewed the education budgetary allocation from 3% to 10% that year. It was further increased to 12% in 2020 and has maintained between 18-22% since then. Also, to expand its education financing capacity, the Federal Government increased the Education tax from 2% to 2.5% through the Finance Act of 2021 and then to 3% through the Finance Act of 2023.

Nested Challenges

It is important to note how interconnected the challenges of the quality gap are and why the gap must be addressed from a holistic perspective. A curriculum redesign necessitates the combination of improved infrastructure, and better quality and qualified teachers. This also rests upon improved financing to set the stage (Figure 5)

Recommendations

- Curriculum Reformation

Curriculum reformation needs to go beyond content changes in subject matter to include changes in instructional objectives and approach. The 21st-century graduate is situated within an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world that necessitates that they are not only prepared with skills that are already in need today but also able to cope with the dynamic nature of the global space with skills for an unknown future. The COVID pandemic exemplified how rapid changes can happen within a short time. If education aims to produce human capital that can continuously drive innovations and global competitiveness in an increasingly VUCA world, then it must aim beyond delivering current knowledge to the ability to synthesize new knowledge. Learners must be able to understand how knowledge is created, not just know what knowledge has already been created. Priority must be given to the learner’s ability to think, over being able to memorize facts or simply perform at a current skill. Curriculum reformation must avoid the ditch of short-term thinking of current needs and aim for longer-term foresight of uncertain future needs. This also calls for the need for more qualitative research in education that helps understand how to create education models that prioritize thinking over memorization within the unique context and challenges of the Nigerian socio-cultural climate.

- Teacher and Teaching Revitalization

Reformation efforts in teaching must aim at 2 interrelated areas:

a. Philosophical reframing of the teaching profession

There needs to be a philosophical reframing of the teaching profession from a professional that “remains unattractive and is most often taken only as the last option” as the Ministerial Strategic Plan for Education (2018-2022) put it. This necessitates a social, economic, and intellectual shift in the framing of the teaching profession. Teaching needs to be seen and valued as the profession straddled with the strategic work of human capital development that it is. Teachers need to be reframed as problem solvers in education who ensure value creation within the human capital ecosystem. This philosophical reframing must be led by the government’s commitment to making the profession more attractive with steps like better and prompt remuneration packages; better commitment to the provision of necessary infrastructure and more. This must also be supported by a necessary shift in the societal frame of teaching to become a more professional line of work. Teaching must become a well-respected, better-supported profession that will attract more talent. Teachers must be seen beyond being “tools in education” to be tweaked for change. The 21st-century teacher cannot be seen as an outsider for whom other stakeholders solve the problems of education and only require him to implement. Teacher education must be done in a way that repositions theteacher as one with both intellectual outlook and professional commitment.

b. Increased teaching effectiveness

To make teaching more effective, there is the need to provide expanded opportunities for teacher’s training. Pre-service teaching training done in National Colleges of Education and Institutes of Education in Universities must be reviewed in line with the expanded needs of the 21st century. There is also the need for continuous professional development for teachers across all tiers of education. In a rapidly changing world, the teacher education curriculum should be redesigned not only to accommodate the need for changes in subject matter knowledge but also the need for better capacity of the teacher to rapidly and continuously self-improve on every form of their teacher knowledge. Especially in Nigeria, with the myriad of societal challenges impart on education quality, teachers must be trained as education solution providers, equipped with intellectual curiosity, professional purview and enhanced thinking, and tools to address the local challenges education is facing in their communities. The teacher of the 21st century must be an education thought leader with enhanced thinking about their work and their role within the economy. Themes such as strategic thinking, design thinking, and social entrepreneurial leadership should become a part of the curriculum of pre-service teacher training and in-service continuous development. There is a need to implement the establishment of Teacher Resource Centres as posited by the Revised National Policy on Education (2013) and expand its work in light of current needs. Education research also needs to be given greater prominence, as lasting reforms in the education sector must be informed by ongoing empirical and qualitative insights into the challenges and ongoing reform practices to be able to understand what is working and what is not.

- Finance Expansion

In the last 4 years, Oyo state has set a remarkable example that increasing the education budgetary allocation is possible. Several tiers of government need to follow this example by prioritizing education. There is a need to reduce the excessive cost of governance in annual

budgets to be able to make judicious use of scarce resources on crucial socioeconomic concerns like education. Also, sources of financing for education need to be expanded beyond the government to incorporate more private investment. Data has shown the growing status of diaspora remittance within the Nigerian financial sector. This shows a promising outlook on the interest of the diaspora community to play a role in strengthening the current Nigerian economy. This interest can be further cultivated by engaging the diaspora in financing education in a more systematic and structured way.

Conclusion

Nigeria is in dire need of education that can strengthen her human capital to strengthen her socioeconomic space in the polity of nations. This kind of education must center quality as a major priority. The better the quality of education, the better the human capital strength of the nation.

References

Ajilore, O.H. (2021). Teachers need Help: The Paucity of Centres for Teaching and Learning in Nigeria. Jean Piaget Conference (USA). DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.20305.30562

Ezeanya-Esiobu, C. (2019). Indigenous Knowledge and Education in Africa. Springer: New York.

Ikiyei, P.K. & Enekeme, A.B. (2023). Student-Teachers’ Interest in the Teaching Profession and the Future of Teaching as a Profession in Nigeria. A Study of Faculty of Education Students, Niger Delta Unversity, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. British Journal of Education,

Learning and Development Psychology 6(1), 12-26.