5th Arthur Mbanefo Annual Lecture

I. INTRODUCTION: THE FUNCTIONS OF EDUCATION

“What is the purpose of education?”, Eleanor Roosevelt asked in an essay she wrote in 1930, three years before she became the First Lady of the United States.

Purpose must be at the heart of education and education systems. That is the only way education can go beyond literacy – important as that is – to develop and transform societies.

The education sector serves as a critical provider of human capital, equipping individuals with the requisite skills and enhancing their intellectual acumen to make meaningful contributions to their communities and nation. Good education works to develop not only the learner’s understanding of established knowledge but also sharpens the learner’s mind and enhances their capacity for thinking, creativity, and innovation so they can become active creators of new knowledge.

Education, however, does not only develop people intellectually; it also plays a vital role in the development of the social dimensions of the person and the citizenry. Well-educated individuals are not only confident to lead fulfilling personal lives but also actively engage in problem-solving within their societal contexts, thereby elevating overall societal welfare and fostering social cohesion. They are not equipped only with intellectual capacity for thinking and knowing, but also with a deepening sense of character, community, and citizenry. Education plays an active role in the socioeconomic development of a nation by actively contributing to educating its people about necessary character, roles, and obligations of citizenship. Education fosters social cohesion and the development of a collective identity necessary for a visionary future.

I therefore agree with experts who have identified five key purposes of education. These are:

- Education for Economic Development. This is the most believed purpose of education. This perspective is rooted in the human capital theory – that the more schooled and educationally qualified we are, the higher our incomes, wages, and our productivity will be.

- Education for Building National Identity and Good Citizenship. Education is an important means that countries use to construct nationhood, a shared sense of unity and purpose for the citizens of the state, beyond physical statehood. It can instill in citizens not just a sense of their entitlements, but also of their responsibilities and obligations as good citizens. Education is a powerful tool to construct and inculcate worldviews – a personal and collective sense of identity, ambition, the values that underpin society and its ambitions for each citizen and collectively, and a nation’s sense of destiny. Without a clear worldview, no nation can rise. We have the examples of the United States and Pax Americana, the British Empire, the Rise of China, and Asia more broadly, the State of Israel and its accomplishments, etc.

- Education as Liberation. This perspective on the purpose of education sees that purpose as that of confronting various kinds of structural oppression and setting people free. Examples include the transatlantic slave trade that lasted for nearly four centuries, colonialism, contemporary racism, gender inequity, and so on. This is the sense in which Martin Luther King defined the purpose of education in his essay in 1947 titled “The Purpose of Education”. The American civil rights leader argued that the purpose of education had to be one of social and political struggle alongside other objectives. Education provided the basis for our struggle for freedom from colonial rule a century ago. Today, although Nigeria became free from colonial rule in 1960, Nigerians are still suppressed and oppressed by maladies such as corruption, tribalism, mediocrity in governance, and the worship of wealth for its own sake, no matter how acquired. In this understanding of the purpose of education, we need the re-education of present and future generations to set our citizens free.

- Education for Well-being. Education advances our social, emotional, physical, mental, and spiritual well-being. This purpose has to do with young people acquiring the knowledge, attitudes and skills that enable them to create positive mental and emotional health for themselves and balanced relationships with others.

- Education for cultural sustenance. Here, education should serve the purpose not just of discarding all aspects of our culture and becoming ever more “westernized”, but in fact hold on to the objectively positive aspects of our indigenous cultures. In this context, education should validate our identities and project it as part of our worldviews.

II. UNDERSTANDING AND ADDRESSING THE CHALLENGES OF NIGERIAN EDUCATION.

Nigeria boasts of a vibrant youth population, with over 60% of its people under the age of 35. This demographic dividend presents a reservoir of human capital ripe for harnessing the nation’s socioeconomic advancement. Human capital, as defined by the World Bank, encompasses the knowledge, skills, and health individuals accrue over their lifetimes, empowering them to fulfill their potential as valuable contributors to society. Yet, the discourse on human capital extends beyond the mere presence of people to encompass their productivity and capacities to generate socioeconomic outputs.

Central to this narrative is the pivotal role of the education sector. Education emerges as a vital conduit for nurturing human capital. Charged with the task of imparting essential skills and honing intellectual acumen, the education sector empowers individuals to make meaningful contributions to their communities and country. Awell-educated populace not only enhances personal fulfillment but also addresses local challenges, elevates societal well-being, and fosters social cohesion.

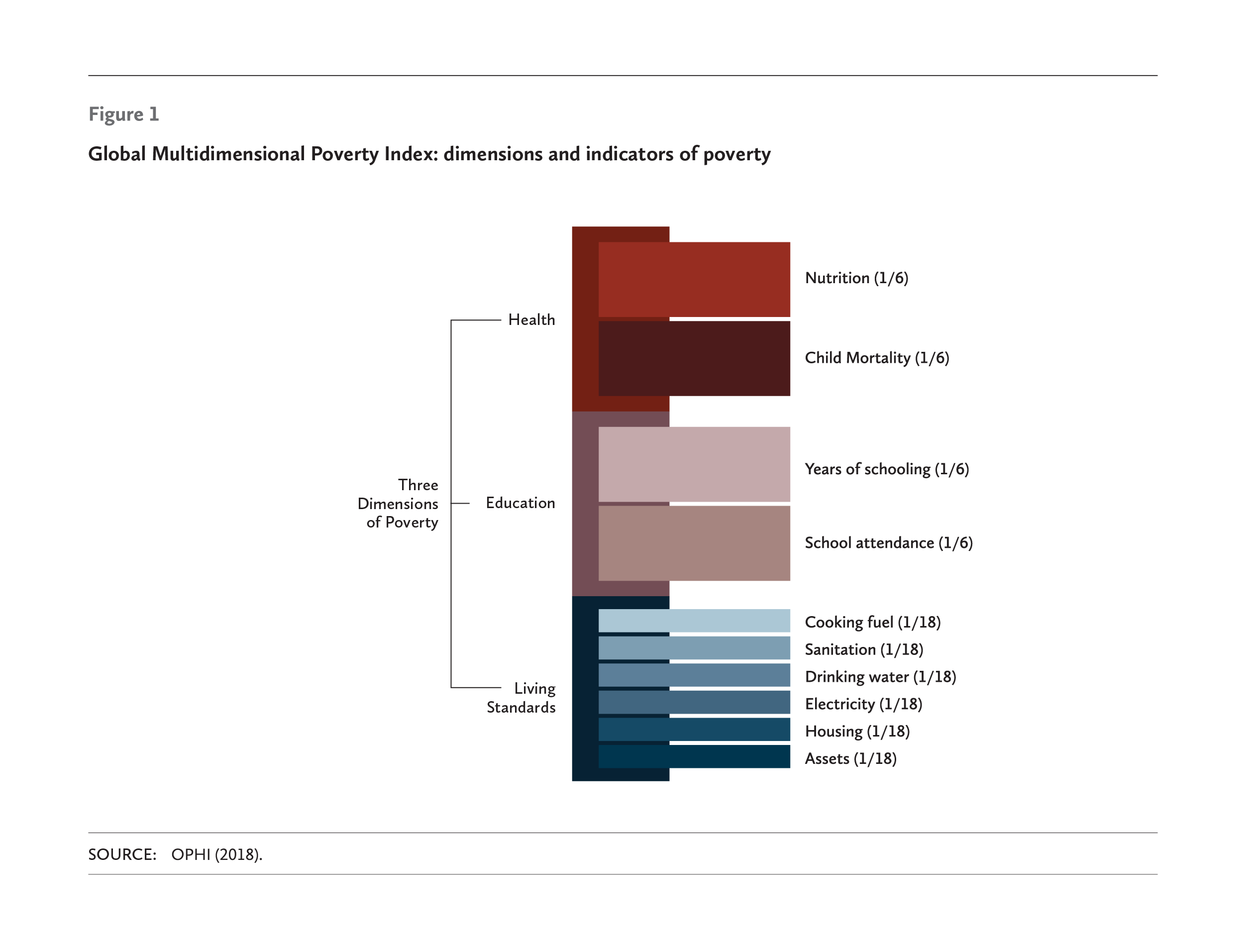

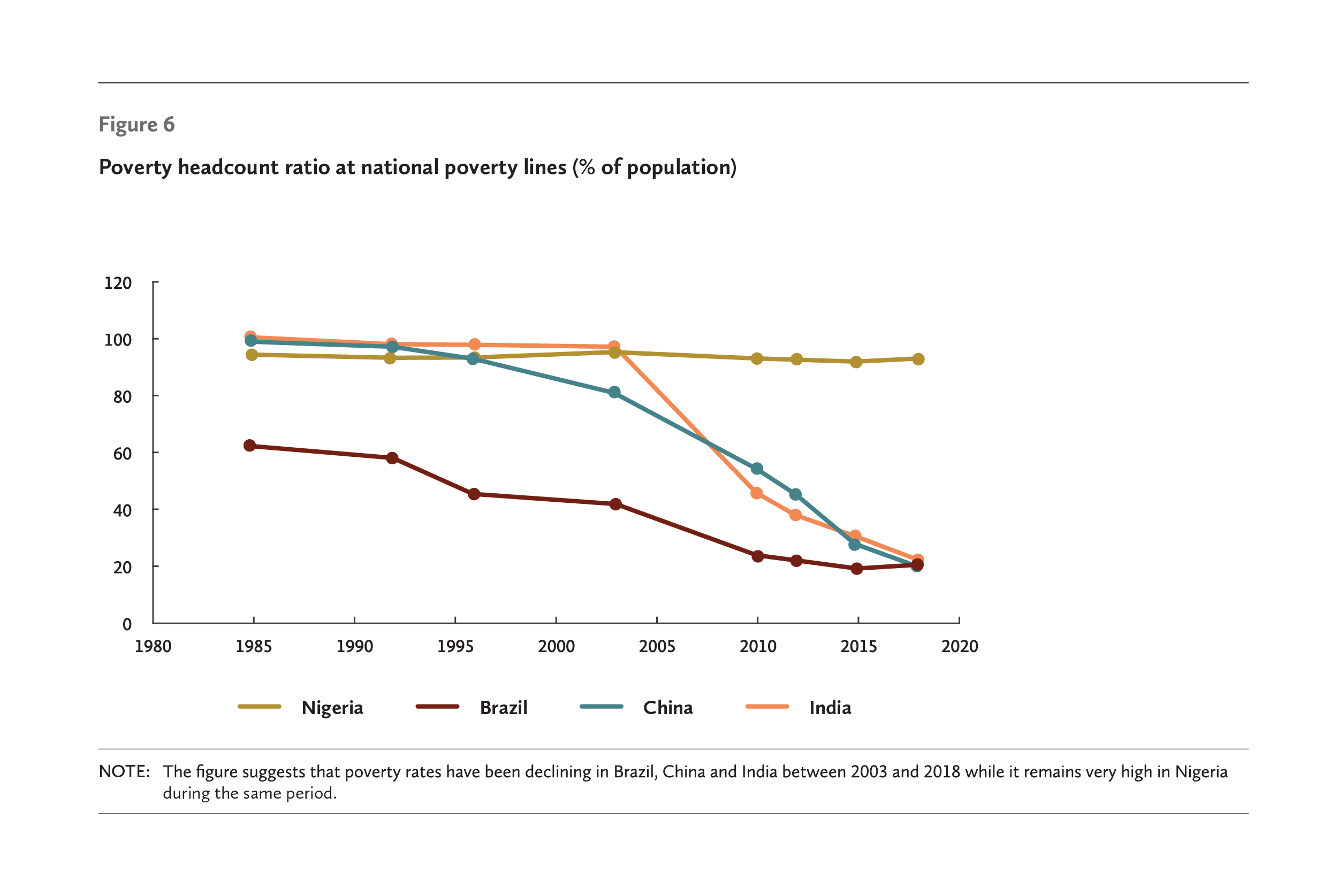

However, the current Nigerian education landscape grapples with myriad challenges, undermining the nation’s human capital potential. As of 2020, Nigeria’s Human Capital Index, as assessed by the World Bank, stood at 0.36, positioning it 168th out of 173 countries globally—a marginal improvement from 0.34 in 2018, where it ranked 152nd out of 157 nations surveyed. This sluggish growth underscores the persistent obstacles hindering the effective education of Nigeria’s populace. For Nigeria to play a significant role on the global stage in the years ahead, it must effectively develop and deploy its human capital to propel national advancement. Given its central role as the primary purveyor of human capital development, the education sector assumes heightened significance in Nigeria’s developmental agenda.

Understanding the intricacies of Nigeria’s educational challenges is vital for devising effective solutions. The education sector comprises numerous interconnected elements, requiring a systematic approach to drive substantial reform. These challenges can be categorized into several areas. One such category encompasses obstacles hindering access to quality education for the Nigerian populace. These hurdles include the escalating number of out-of-school children, low rates of educational completion, limited transitions between educational levels, adult illiteracy, and the provision of education during emergencies.

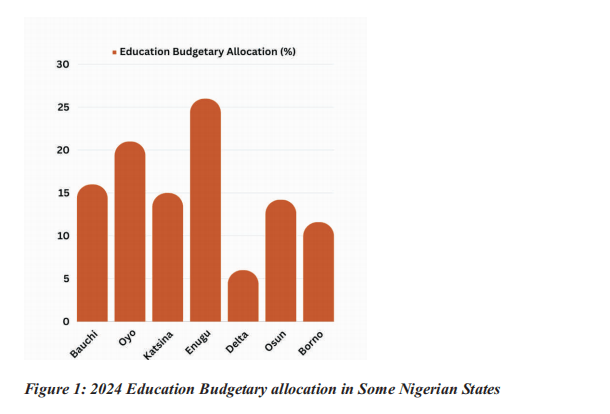

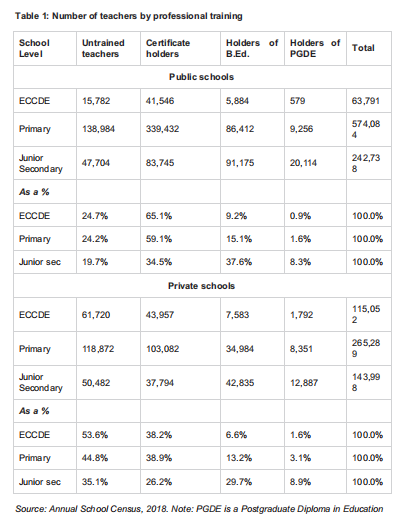

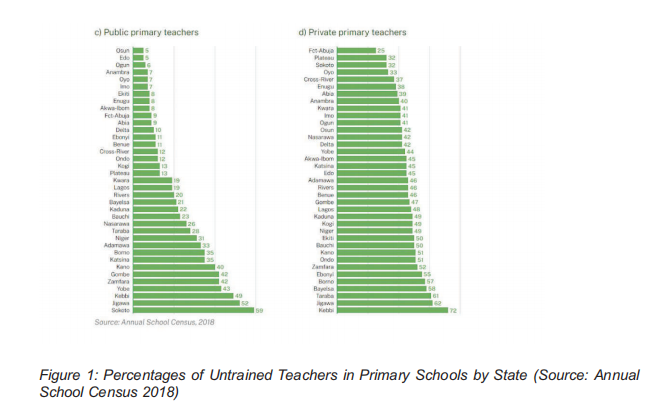

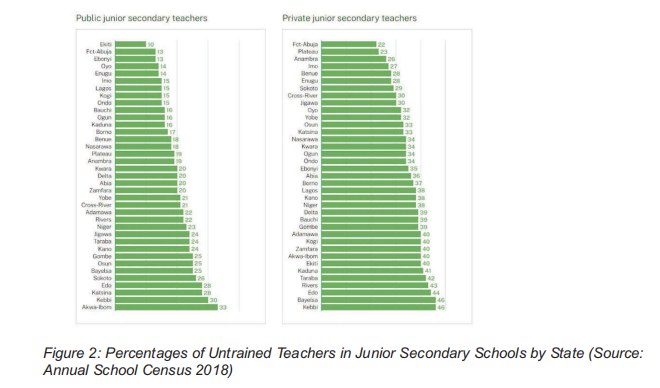

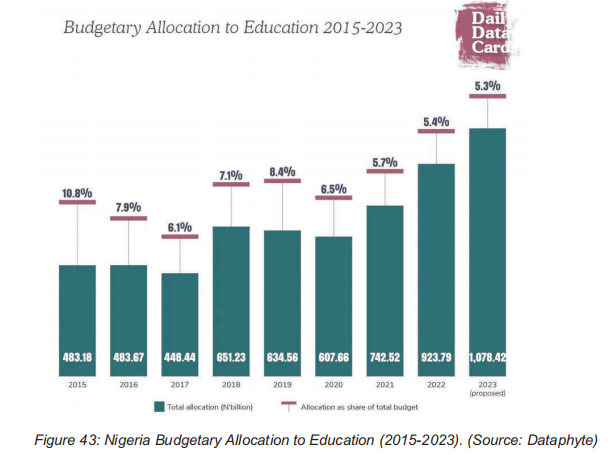

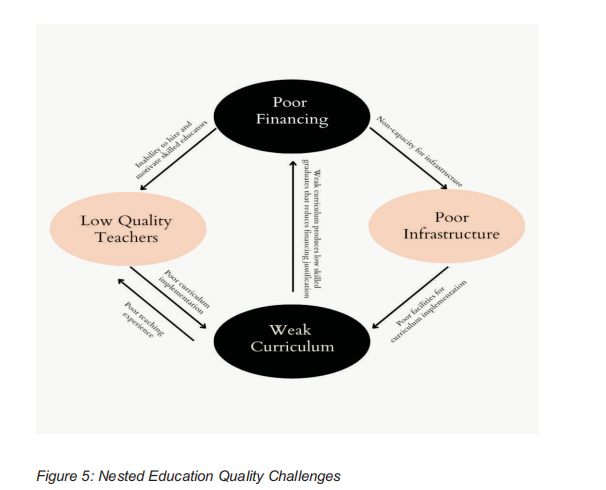

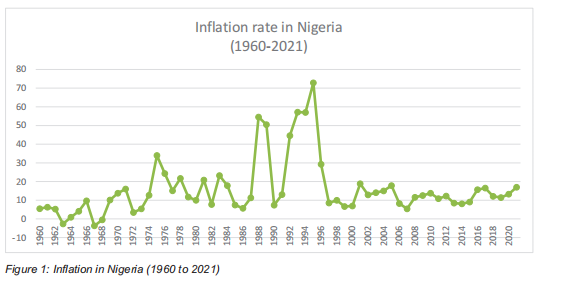

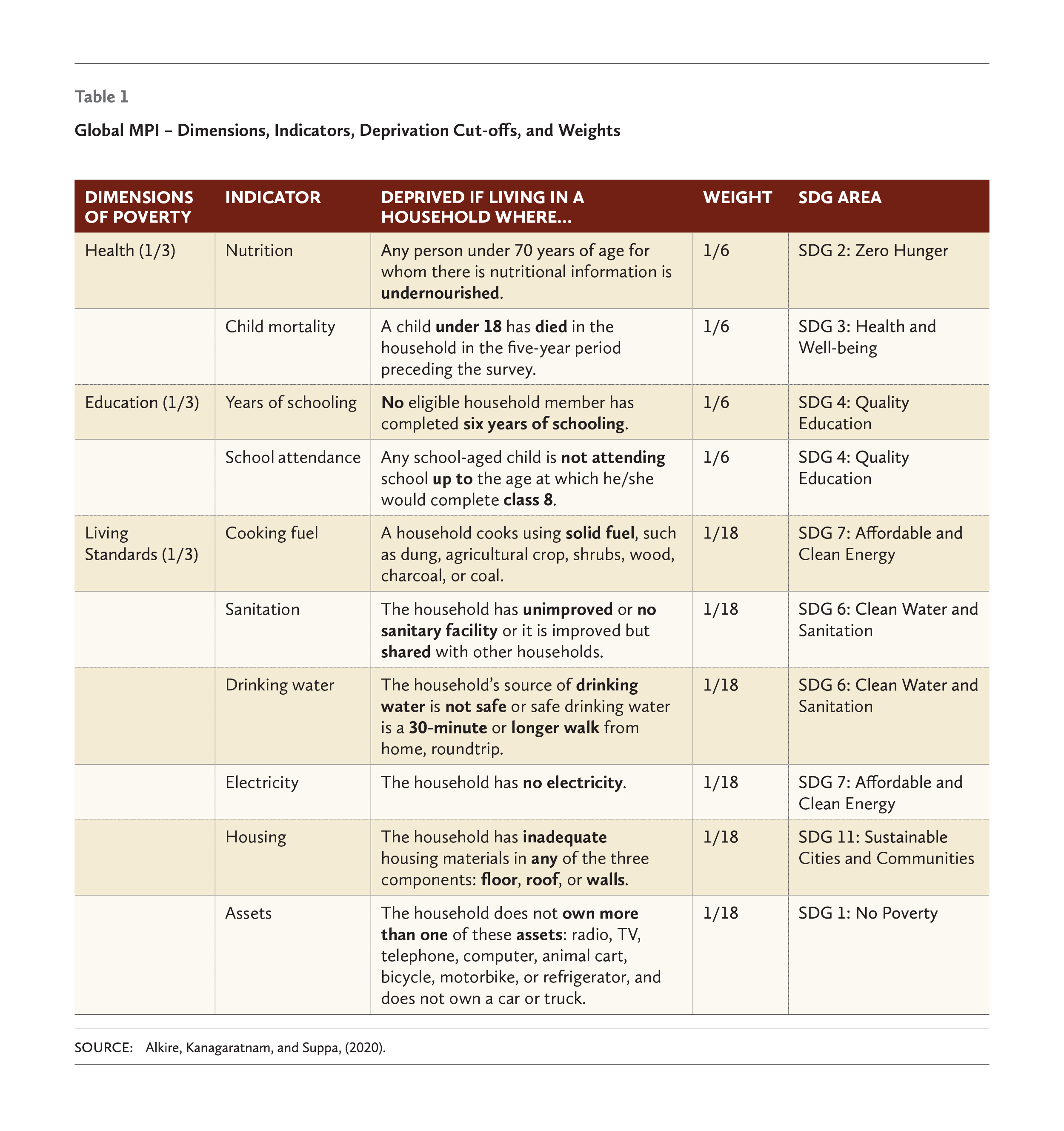

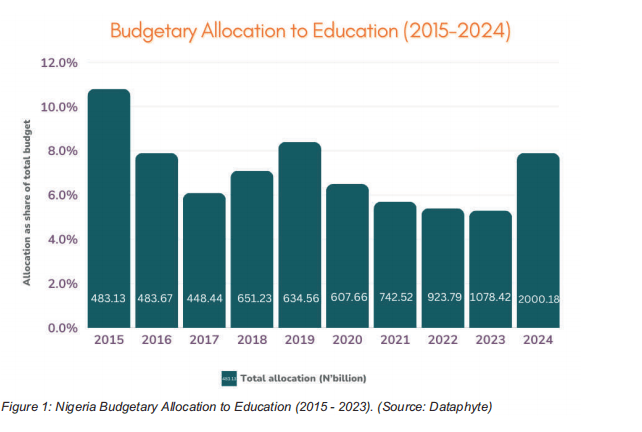

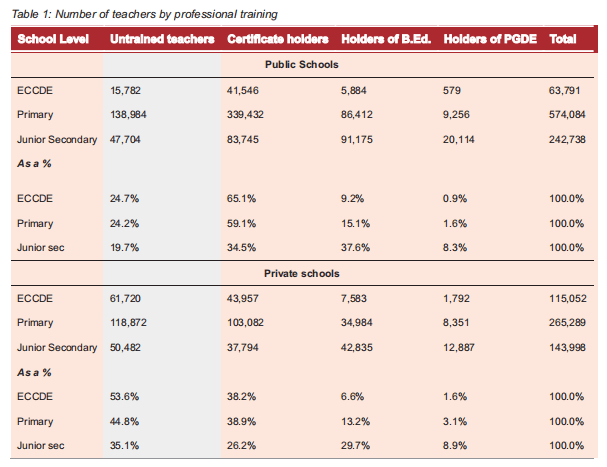

Another set of challenges pertains to the erosion of education quality, resulting in insufficient capacity-building within the existing educational framework. Among these challenges is inadequate financing. Despite UNESCO’s recommendation that developing nations allocate 10-15% of their budgets to the education sector, Nigeria’s education budget allocation is a low 5.3% in 2023 (Figure 1). Additionally, both the World Bank and UNESCO have disclosed that a minimum of 20% of teachers in public basic education institutions in Nigeria lack the necessary qualifications. This percentage nearly doubles in private schools (Table 1). Furthermore, the quality of Nigeria’s education system suffers from deficient educational infrastructure.

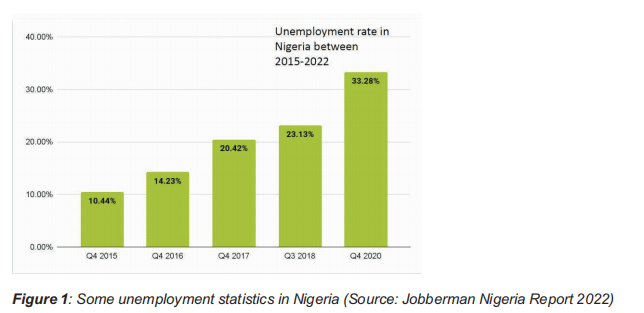

Another significant category of challenges revolves around the human capital implications stemming from inadequate access to and quality of education. These challenges include the disconnect between academia and industry, diminishing socio-emotional attachment to education among young individuals, rising unemployment rates, and the issue of unemployability. These challenges contribute to a myriad of other interconnected problems within the education system.

Addressing the challenges within the Nigerian education system requires a multifaceted approach. Acritical first step, however, is recognizing the lack of clear objectives within the system. Establishing these objectives is vital to driving progress and development. The reform movement must be grounded in precise objectives that can guide efforts toward meaningful change. It’s essential to determine the necessary reforms and the desired outcomes of an improved education system. Given Nigeria’s context, needs, and trajectory, three fundamental objectives are paramount for driving development and should serve as the cornerstone of education reform efforts. These objectives are:

- Literacy

Nigerian education reforms must emphasize both foundational and adult literacy. Several challenges have attacked foundational literacy. For instance, UNESCO has estimated that there are approximately 20 million out-of-school children aged 6-18 in Nigeria, which is a significant increase from the 13.7 million reported by the World Bank in 2013. This means that one out of every 12 out-of-school children worldwide is Nigerian. In 2019, the gross enrollment rate for primary school children at the required age was 68%, while it was 54.4% for secondary school children.

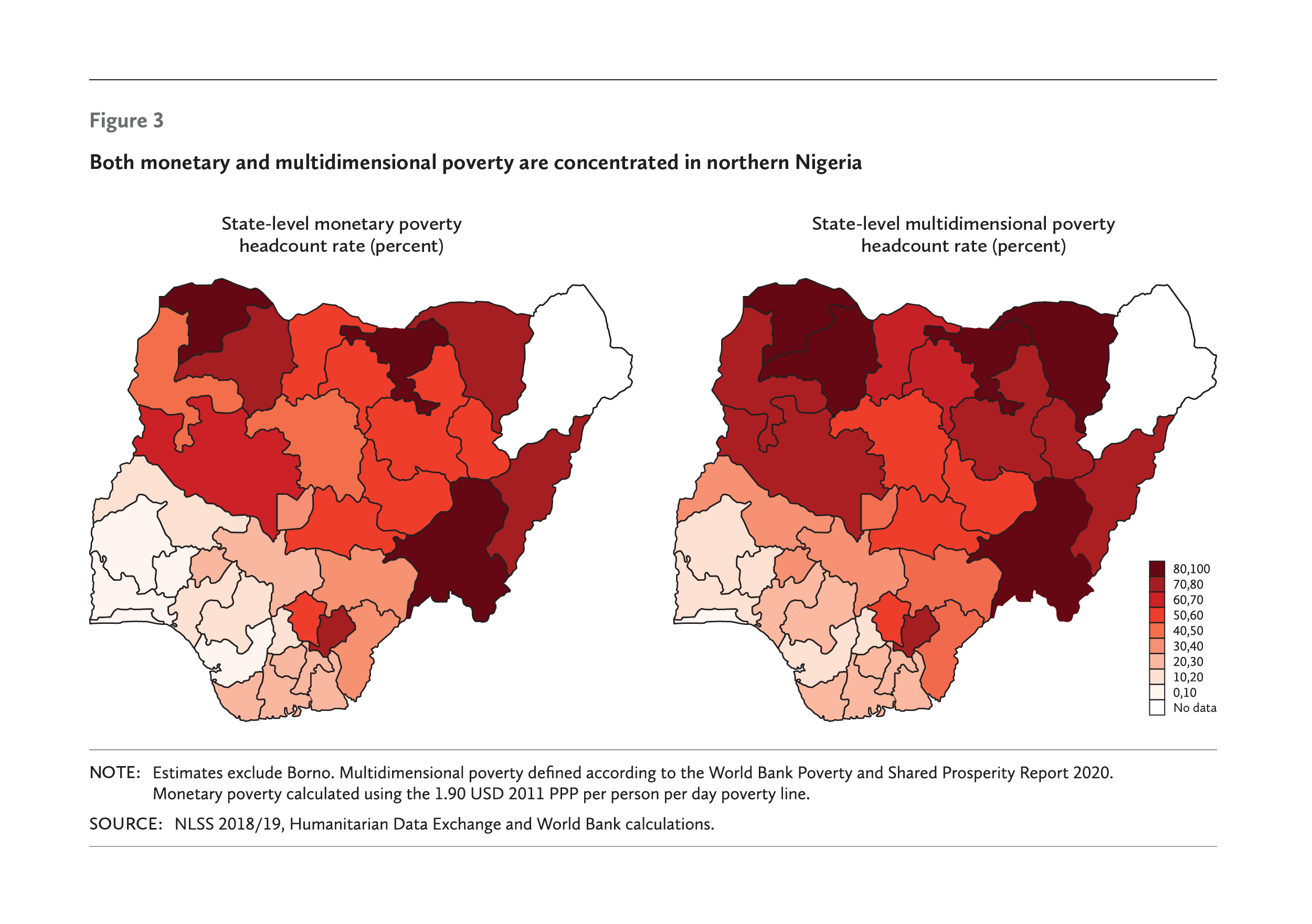

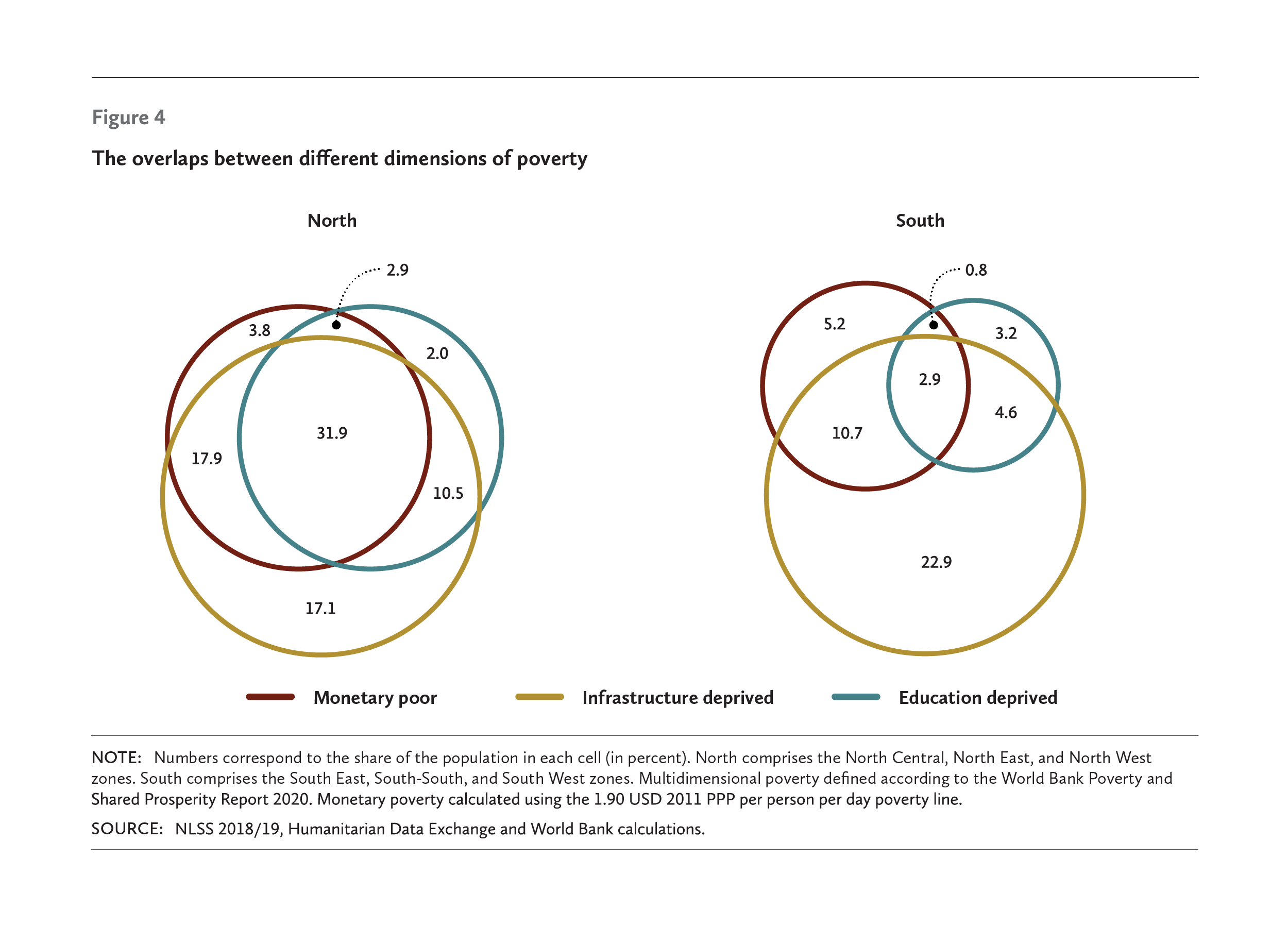

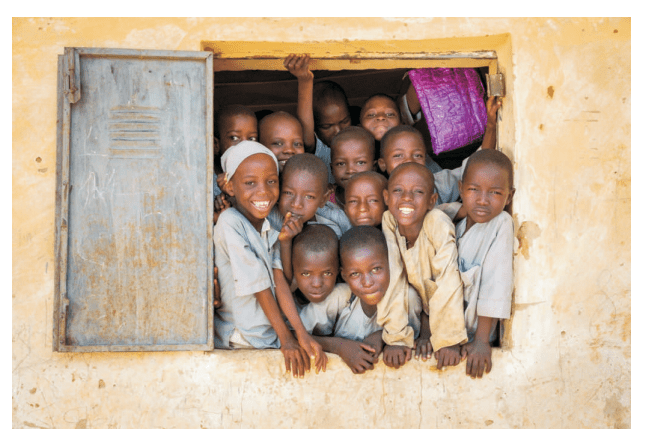

However, these figures do not fully capture the disparities in educational access across different regions, as the net primary school attendance rate drops to 53% in Northern Nigeria, according to UNICEF. The situation is particularly dire for girls, with more than half of girls in the Northeast and Northwest regions of Nigeria not attending school. Some states in these regions have female primary net attendance rates as low as 47.3%. The challenges contributing to the Out-of-School Children (OOSC) dilemma stem from both overarching and region-specific factors. Generally, barriers to children’s education include poverty and insufficient educational infrastructure.

When viewed through a geopolitical lens, these obstacles vary in nature and intensity across different regions. In the Northern areas, socio-cultural complexities exacerbate the situation, with insurgency emerging as a prominent concern. There were approximately 25 terrorist attacks targeting schools in the North in 2021, resulting in the abduction of 1,440 children and the tragic loss of at least 16 lives. In March 2021, around 618 schools in Kano, Niger, Katsina, Sokoto, Zamfara, and Yobe states were forced to close due to fears of attacks and kidnappings of students and staff. Additionally, cultural perceptions associating schooling with Western influences, negative attitudes towards female education, and religious sentiments further compound the issue.

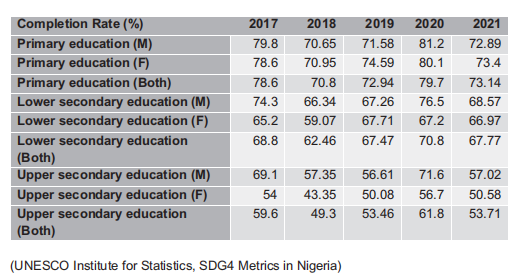

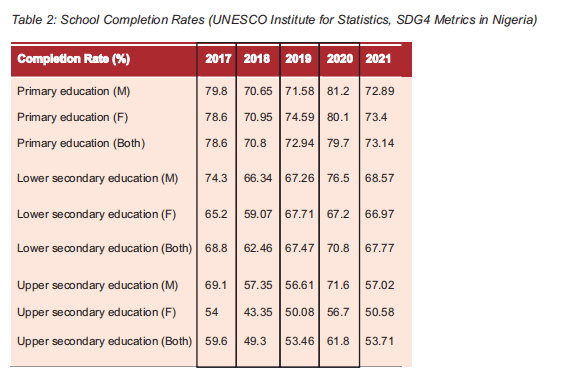

Low Literacy levels are also influenced by school completion rates. UBEC’s 2018 Education Profile Indicators revealed low completion rates for primary, junior secondary and senior secondary education in Nigeria. Disparities existed across different geopolitical zones, with the North Central region having a low primary school completion rate of 63.84%. UNESCO’s data for 2018 (Table 2) showed primary school completion at 70.80%, junior secondary at 62.46%, and senior secondary at 49.30%, all lower than 2010 figures. By 2021, slight improvements were seen with primary school completion at 73.14%, junior secondary at 67.77%, and senior secondary at 53.71%, though a reversal in progress was noted due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

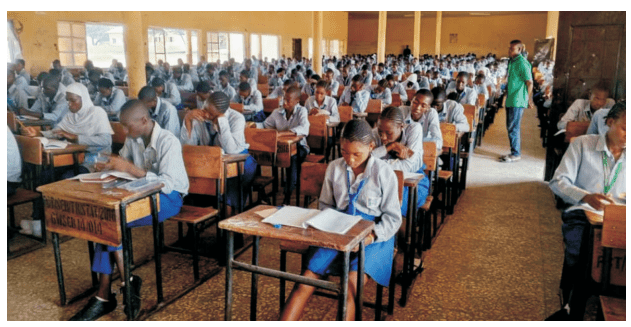

Gender disparities were evident, with a widening gap between male and female students as they transitioned from primary to secondary school, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions to ensure equal access to education. The accessibility of education becomes increasingly challenging as children and youth progress through the various levels of education. This trend is evidenced by a noticeable decline in attendance rates, dropping from 68% in primary school to 54% in secondary school, and further plummeting to approximately 12% in tertiary education.

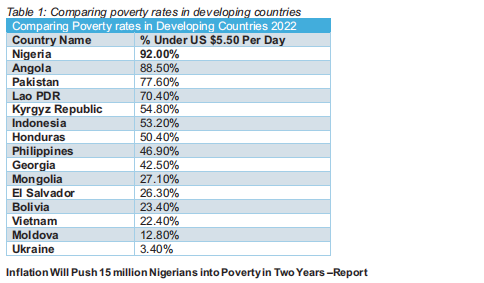

Tertiary education is the least attainable form of education in Nigeria, primarily due to a range of factors. Among these factors, the high cost of tertiary education stands out as a significant barrier. Annual tuition fees at Nigerian universities typically range from $200 to $5000, a stark contrast to the socioeconomic conditions of the country, where more than 33% of the population lives on less than $2 per day.

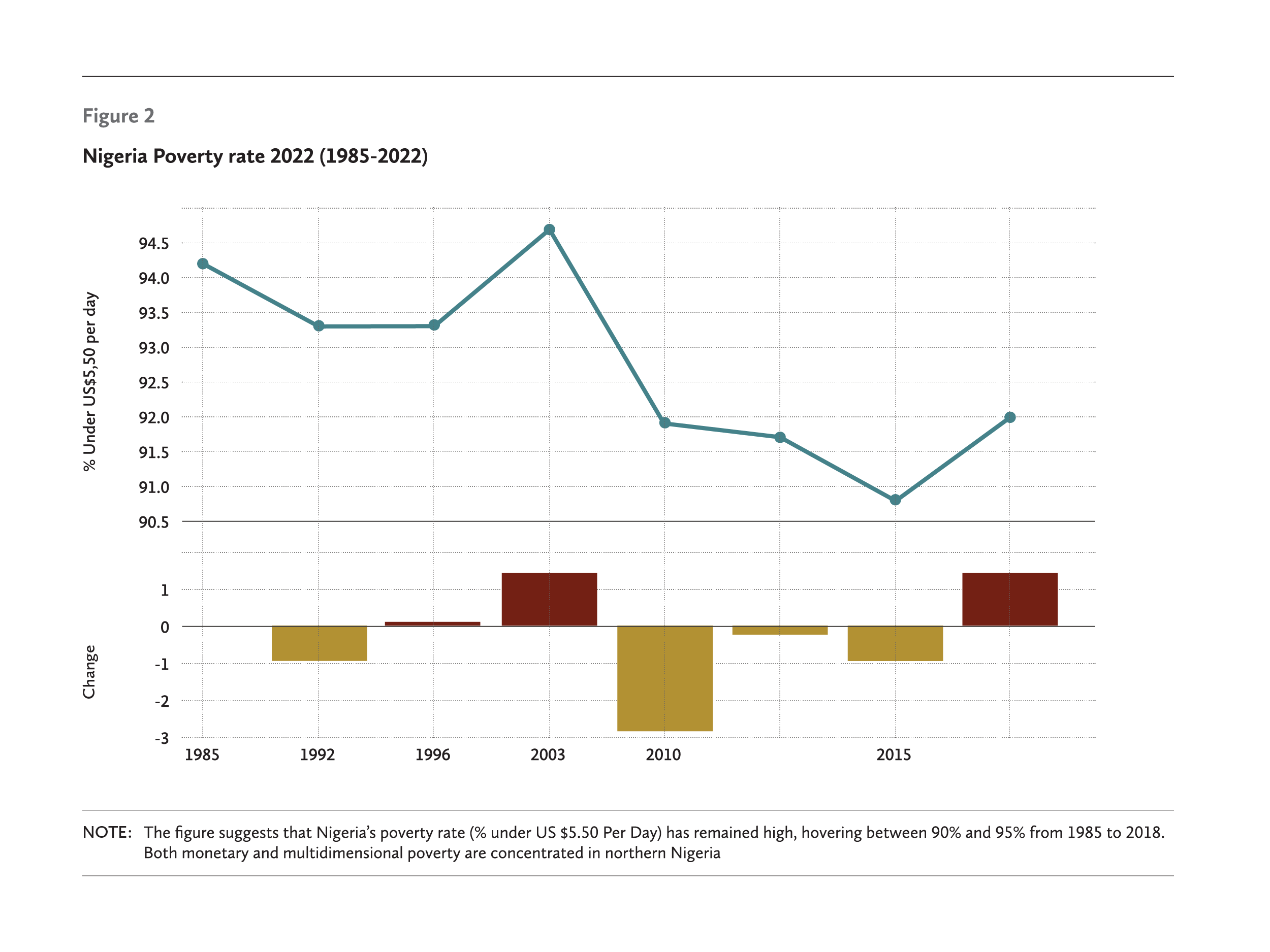

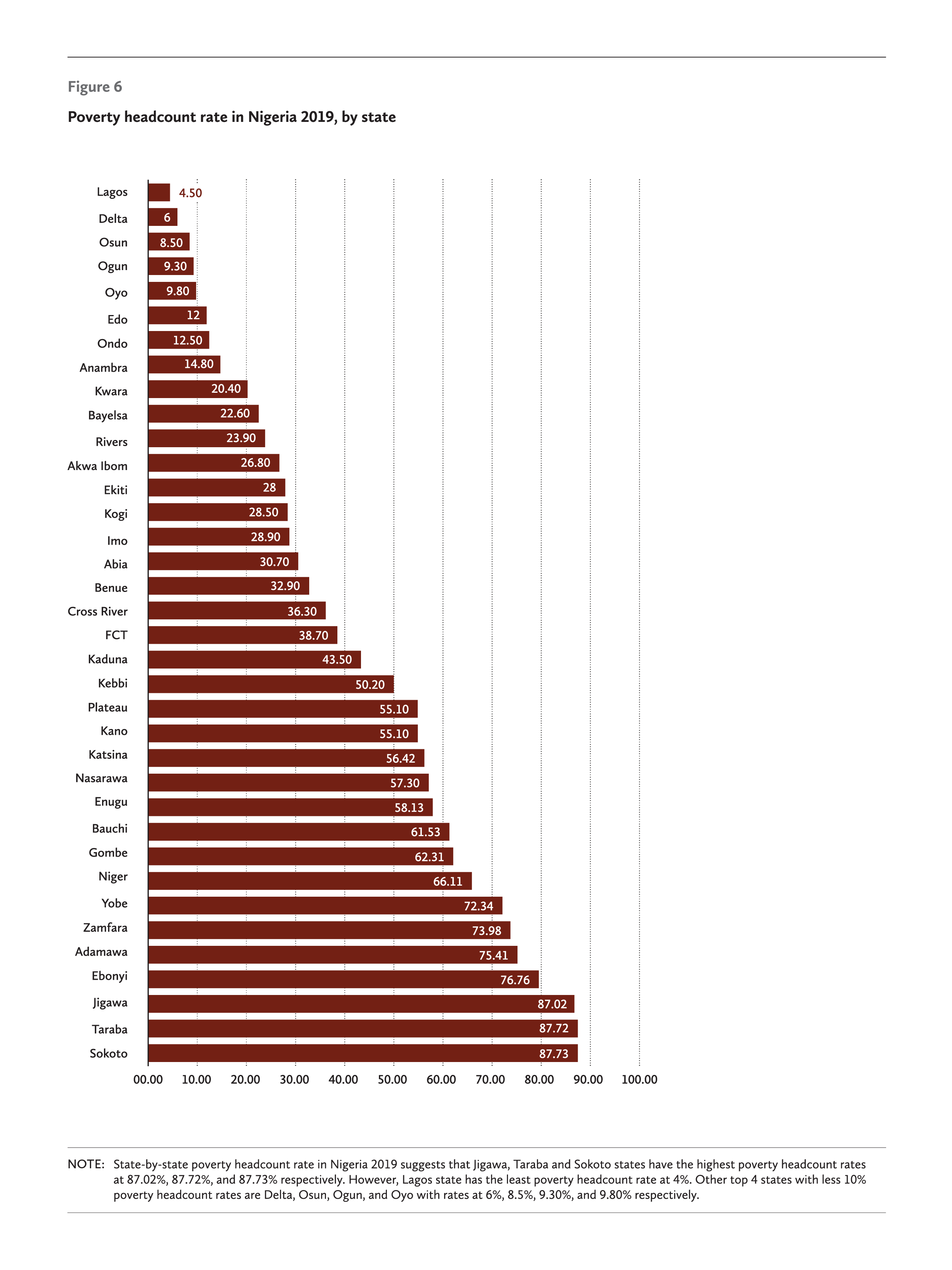

The challenges of illiteracy in Nigeria are beyond the foundational levels. Adult illiteracy persists in Nigeria despite ongoing efforts to improve literacy rates. According to UNESCO, Nigeria’s overall literacy rate was approximately 62% in 2018, indicating a substantial portion of the adult population lacks basic reading and writing skills. Illiteracy rates across the country exhibit regional disparities with the rates generally higher in the northern states when compared to the southern regions. For example, in some northern states like Katsina and Borno, the adult literacy rate is below 30%, while in the southern states like Lagos and Ogun, it exceeds 80%.

Moreover, gender inequality exacerbates the problem, with women generally experiencing lower literacy rates than men, particularly in rural areas where traditional gender roles may limit girls’ access to education. According to UNICEF, in some northern states like Kano and Sokoto, the female literacy rate can be as low as 14%, compared to over 60% for males. Rural communities also bear the brunt of illiteracy, as limited infrastructure and fewer educational opportunities hinder literacy development. Consequently, illiteracy tends to be more prevalent in rural areas than in urban centers.

The economic implications of adult illiteracy are significant, as it restricts individuals’ access to higher-paying jobs and hampers their ability to participate fully in the workforce, perpetuating the cycle of poverty. According to the World Bank, each additional year of education for an individual can increase their income by up to 10%. Furthermore, illiteracy impacts health outcomes and overall development, as individuals with low literacy levels struggle to understand health information and engage in civic activities. Despite government efforts to address adult illiteracy through initiatives such as adult education programs and literacy campaigns, challenges such as limited resources, infrastructure deficits, and socio-cultural barriers persist. It becomes imperative, therefore, that literacy, both at the foundational and adult levels, be a core objective of the nation’s education reformation.

- National Ethos and Values:

The national ethos of a nation encapsulates its core values, beliefs, and ideals, shaping its collective identity and guiding its actions on both individual and societal levels. The national ethos of a country provides both sociological and ideological definitions to that country and stands it out in the comity of nations. It serves as the compass, influencing policies, behaviors, and interactions within the nation and between it and other countries. It also serves as the ideal vision from which her citizens and communities can build their personal and communal visions. Essentially, the national ethos encapsulates the core principles that characterize the nation’s character and aspirations. For instance, the national ethos of the United States is rooted in the ideologies of liberty, equality, democracy, and opportunity that encompass the ideals of individual rights, freedom of speech, religious tolerance, and the pursuit of happiness towards the goals of diversity, innovation, and resilience.

Chapter 2 Section 23 of the Nigerian Constitution describes the national ethics of the nation as Discipline, Integrity, Dignity of Labor, Social, Justice, Religious Tolerance, Self-reliance and Patriotism. Other national values spread across several sources, including the constitution and official government statements include cultural diversity, respect for the rule of law, democracy, patriotism, faith and spirituality among others.

Cultivating and disseminating a thorough understanding of the national ethos of the country should be a major objective of the Nigerian education system. Education should play a role in the acculturation of citizens towards the collective identity of the nation. Thus, there is a need to align the education systems towards the promotion of the national ethos.

- Skills

The education system of Nigeria must put skill development right at its center. Education must go beyond rote memorization of facts to helping learners acquire various forms of skills that make them form a formidable human capital for the nation. Educated citizens must be skilled to be able to create individual livelihoods, community wealth, and national value chains and thus effectively contribute to the economic transformation and global competitiveness of the nation, especially considering the 4th Industrial Revolution. There are at least 5 kinds of skills that are crucial for education to help develop among the nation’s educated citizens:

- Technological Skills: In the 4IR, technology plays a central role in driving economic growth and innovation. Without adequate technological skills, Nigeria may struggle to adopt and leverage emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the Internet of Things (IoT) to improve productivity, efficiency, and competitiveness across various industries. This lack of technological proficiency can hinder the development of advanced manufacturing, digital services, and other high-value sectors critical for economic transformation.

- Scientific Skills: Scientific knowledge and research are essential for innovation and the development of new products, processes, and technologies. Without a strong base of scientific skills, Nigeria may face challenges in conducting cutting-edge research, developing indigenous technologies, and addressing complex societal problems. This can limit the country’s ability to create value-added products, attract investment, and compete in knowledge-intensive industries globally.

iii. Vocational Skills: Vocational skills are crucial for meeting the demands of a rapidly evolving labor market and supporting industries such as construction, manufacturing, and services. Without a skilled workforce in areas such as plumbing, welding, electrical work, and automotive repair, Nigeria may struggle to meet infrastructure needs, maintain industrial machinery, and provide essential services. This can impede economic development and hinder efforts to build resilient and sustainable communities.

iv. Entrepreneurial Skills: Entrepreneurship is a driving force behind economic growth, job creation, and innovation. Without a culture of entrepreneurship and the necessary skills to start and grow businesses, Nigeria may struggle to unleash the full potential of its human capital and natural resources. Lack of entrepreneurial skills can inhibit the creation of new ventures, the scaling of existing enterprises, and the development of vibrant ecosystems that foster innovation and collaboration. A focus on developing vocational skills, when combined with entrepreneurial skills and efficient access to capital, will play an important role in boosting employment in Nigeria, as self-employment is one of the most potent methods of reducing unemployment.

v. Interpersonal/Soft Skills: These encompass a range of personal attributes, attitudes, and abilities that facilitate effective interactions with others, adept navigation of social situations, and success across various life and work domains. Unlike job-specific technical skills, soft skills are transferable and relevant across different roles and environments. They include skills such as communication, problem-solving, adaptability, leadership, time management, and emotional intelligence. These capabilities are vital for fostering relationships, collaborating effectively, managing conflicts, and attaining both personal and professional achievements. Soft skills complement technical proficiency and are highly prized by employers in today’s ever evolving and interconnected world. Without appropriate soft skills, educated Nigerians might struggle to sustain their jobs and/or ventures, adapt to changing global workforce dynamics, and innovate for the long haul.

Nigerian Tertiary Education particularly needs to foster integration between academia and the industry. While academia is traditionally expected to serve as a supplier of human capital and a catalyst for research-based innovation in industries, this synergy has not been fully realized within the Nigerian tertiary education system. Students in higher education often have limited exposure to the professional world, and the curriculum tends to prioritize academic theory over the development of practical skills required in the modern world of work. It is therefore pertinent that skill development becomes a core objective of education for Nigeria to position itself as a competitive player in the global economy and achieve sustainable economic transformation. Investing in education, training, research and development, and supportive policies can help develop a skilled workforce equipped to drive innovation, create value, and thrive in the 4IR.

II. IS NIGERIA’S CURRENT EDUCATION POLICY FIT FOR PURPOSE?

The impetus for a national education policy arose from the 1969 National Curriculum Conference, which convened a diverse group of Nigerians. This gathering was prompted by widespread dissatisfaction with the existing education system, which had become disconnected from national needs, aspirations, and goals.

The conference, occurring amidst the Civil War, served as a pivotal moment for the development of Nigeria’s indigenous education system and continues to underpin the nation’s educational philosophy. Beyond intentionally tailoring an educational framework to align with the nation’s cultural context and practical requirements, a notable aspect of this conference was its inclusivity, drawing participants from diverse sectors of Nigerian society beyond academia and government.

Following the National Curriculum Conference, a seminar was held involving representatives from various interest groups across Nigeria, including voluntary agencies and external bodies. The seminar deliberated on the essential components of a national education policy suitable for an independent and sovereign Nigeria. The result was a draft document that, after receiving input from states and other interest groups, culminated in the publication of the National Policy on Education in 1977. Subsequent editions followed in 1981 and 1993. The fourth edition, released in 2004, was prompted by policy innovations and changes, as well as the need to update the previous edition from 1998. The subsequent editions, 2007 and 2013, reflecting the evolving landscape of social change and educational demands, incorporated recent developments such as:

- Rescinding the suspension order on Open and Distance Learning programs by the Government.

- Strengthening and expanding the National Mathematics Centre (NMC).

- Establishment of the Teachers Registration Council (TRC).

- Integration of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) into the school system.

Inclusion of French Language in the primary and secondary school curricula as a second official language.

Specification of the minimum number of subjects required for candidates.

Incorporating basic education into the school program to ensure equal opportunity and implementation of Universal Basic Education (UBE).

Enhancing the science, technical and vocational education scheme to optimize national educational performance.

Updating the policy to reflect current best practices in education, among other changes.

Nigeria’s education policy has evolved over the years, aiming to address various challenges in the education sector, such as access, quality, and relevance. In recent years, Nigeria’s education policy has been undergoing reforms to improve the quality of education and make it more relevant to the needs of the society and the economy. Some key aspects of the current education policy include:

i.Universal Basic Education (UBE) Policy: Implemented to ensure that every Nigerian child has access to free and compulsory basic education. This policy covers the first nine years of formal education, comprising six years of primary education and three years of junior secondary education.

ii. Tertiary Education Policy: Nigeria has various tertiary education institutions, including universities, polytechnics, and colleges of education. The policy aims to expand access to tertiary education while also ensuring quality and relevance. Efforts have been made to improve infrastructure, curriculum, and faculty quality in these institutions.

iii. Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET): Recognizing the importance of skills development for economic growth and youth empowerment, Nigeria has been placing more emphasis on TVET. Efforts have been made to improve the quality and relevance of vocational education to align with industry needs.

iv.Curriculum Reforms: There have been ongoing efforts to review and update the national curriculum to make it more responsive to the needs of the society and economy. This includes integrating technology, entrepreneurship, and critical thinking skills into the curriculum.

v.Teacher Training and Capacity Building: Improving the quality of teachers is crucial for enhancing the overall quality of education. The government has been investing in teacher training and professional development programs to equip educators with the necessary skills and knowledge.

Despite these efforts, Nigeria’s education system still faces many significant challenges, including inadequate funding, infrastructure deficits, teacher shortages, and issues of equity and access, particularly in rural areas. Additionally, there are concerns about the quality and relevance of the curriculum and the effectiveness of implementation. So, it continues to beg the question if the current national policy on education is truly fit for its purpose of shaping the nation’s education system as the vital national human capital supplier in the 21st century.

A full 55 years later, the Nigerian education system still largely runs on the 1969 vision. The National Policy on Education, even with all its revision, still imbibes a view of education that doesn’t reflect much of the globalization trends of the 21st-century world. Its most current version was published in 2013, i.e. 11 years ago – a testament to the fact that much of our current education vision is playing catch up with rapidly changing global dynamics.

In addition, the National Education Policy suffers from implementation challenges. Innovative policy reforms are sometimes crippled at the implementation stages due to factors such as lack of adequate human capacity, inadequate funding, and corruption. At other times, implementation of policies is sometimes slowed down or completely side-stepped because of weak political will and vested interests within the community of stakeholders responsible for implementation. Despite the creditable objectives and structure of education in Nigeria, all indications point to the fact that the Nigerian system of education failures is on the yearly increase which can be effectively attributed to problems of policy implementation.

IV.NIGERIA EDUCATION POLICY AND GLOBAL COMPETITIVENESS: LESSONS FROM OTHER COUNTRIES

The socioeconomic strength of any country is directly correlated to the strength of its education system. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in its Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) which assesses 15-year-olds’ abilities in reading, mathematics, and science, found a clear correlation between the academic achievement and economic outcomes of a country. Generally, developed countries with strong education systems demonstrate some common key characteristics, including:

i. Implementation of rigorous standards and cohesive curricula designed to prepare students for a competitive global economy. Teaching and learning methodologies prioritize critical thinking, interdisciplinary connections, and fostering innovation.

ii. A commitment to both equity and excellence in education. Highly ranked nations ensure that all students, regardless of socio-economic background, have access to high-quality education.

iii.Rigorous recruitment and training processes for teachers and school leaders. Only individuals with exceptional academic achievements are selected to join the education profession, and continuous professional development opportunities are provided to maintain a focus on shared educational objectives. Compensation and career advancement structures are clearly defined.

iv.A strong emphasis on mathematics and science education, starting from the early stages of primary schooling and progressing throughout the educational journey.

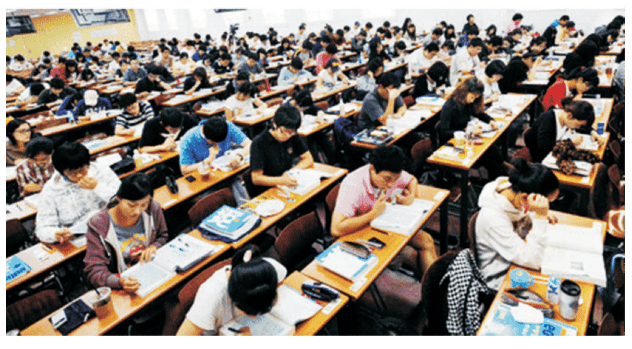

v. A dedication to extended learning time and academic effort. Asian students, for example, invest more time in their education compared to their American counterparts, leading to a deeper academic foundation.

vi.Astrong commitment to adequate financing of education.

High-Performing Education Systems: Case Studies of Israel and South Korea

In 2012, Israel ranked second among Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (tied with Japan and after Canada) for the percentage of 25 to 64-year-olds that have attained tertiary education with 46 percent compared with the OECD average of 32 percent. In addition, nearly twice as many Israelis aged 55–64 held a higher education degree compared to other OECD countries, with 47 percent holding an academic degree compared with the OECD average of 25%. It ranks fifth among OECD countries for the total expenditure on educational institutions as a percentage of GDP.

In 2011, the country spent 7.3% of its GDP on all levels of education, comparatively more than the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development average of 6.3%. As a result, Israel has fostered an education system that helped transform the country and rapidly grow its economy over the past 70 years. In 2019, OECD countries spent on average 4.9% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on primary to tertiary educational institutions. In Israel, the corresponding share was 6.2%. Between 2008 and 2019, funding for educational institutions from all sources grew by 74% in Israel. Over the same period, the increase in GDP was lower with 52%. Consequently, expenditure on educational institutions as a share of GDP grew by 0.8 percentage points over the same time.

South Korea is another top-performing OECD country in reading, literacy, mathematics, and sciences, with the average student scoring about 519, compared with the OECD average of 493, which ranks Korean education at ninth place in the world. The country has one of the world’s highest-educated labor forces among OECD countries and is well known for its high standard of education, resulting in the nation being consistently ranked amongst the top for global education.

The main driving force behind Korea’s development is the government’s investment in human resources. Consequently, Korea can provide the necessary skilled workforce at the right time through vocational education and training and is now preparing for the future by tackling issues

posed by the 4th industrial revolution. The Korean government has launched and implemented two major education policies: The Free Semester Program (FSP) and the SMART Initiative. Through such efforts, Korea aims to meet changing industrial demands and foster a creative economy. The Free Semester Program (FSP) was implemented to address the identified shortcomings in its education system, including academic stress, teacher-centric teaching/learning, learning confined to textbook and class, test-based assessment, and teacher-dominant education manpower. First announced in 2013, FSP aimed at developing competencies for the 4th industrial revolution, such as creativity, problem-solving skills, higher-order thinking skills, and social-emotional skills, with four objectives by offering students a chance to find their dreams and talent and continuously reflect upon and develop themselves through experiences of exploring and designing their aptitude and future. Diverting from a competition-centered education, FSP enables self-leading creative learning and the development of creativity, personality, and social skills through a shift towards student-centered teaching and learning. Rather than traditional lecture-based classes, students are engaged in solving complex problems through project-based learning and debates. FSP was initiated in 43 schools and continually expanded to all 3204 middle schools (100% of all public middle schools) as its overall positive impact was recognized.

Korea also launched its Self-directed, Motivated, Adaptive, Resource-enriched, and Technology-embedded (SMART) Education initiative in 2011 to customize education systems and bridge the gap between these new and innovative fields and the education sector in a way that fosters learner capacities for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The key goal of implementing the SMART Education initiative was to digitize educational content by 2015, reflecting modern changes of the 21st century and to utilize ICTas a primary medium of learning.

Key Lessons for Nigeria

Nigeria’s 21st-century education policy should reflect a commitment to providing equitable, inclusive, and high-quality education that empowers individuals, strengthens communities, and drives national development. Taking lessons from countries with strong education systems, the nation’s education policy should prioritize several key areas, including:

i.Digital Literacy: Incorporating technology into teaching and learning processes to enhance engagement, access to information, and innovation to equip students with digital skills essential for the modern workforce.

ii.Quality of Education: Ensuring that the curriculum is up-to-date, relevant, and of high quality to meet international standards and equips students with the knowledge and skills needed to succeed in a globalized economy.

iii. Access to Education: Addressing barriers to education such as poverty, gender inequality, and geographical disparities to ensure equal access to quality education for all children.

iv.Skills Development: Focusing on developing critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, and collaboration skills to prepare students for the challenges of the future workplace.

v.Teacher Training: Providing continuous professional development and support for teachers to enhance their skills, motivation, and well-being in delivering

effective and engaging lessons using modern teaching methods and technologies.

vi.Partnerships and Collaboration: Collaborating with various stakeholders, including government agencies, private sector organizations, civil society, and international partners, to leverage resources, expertise, and best practices in education delivery and improvement.

vii. STEM Education: Promoting Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education to cultivate a workforce capable of driving innovation and technological advancement.

viii. Entrepreneurship Education: Introducing entrepreneurship education to foster an entrepreneurial mindset among students and empower them to create jobs and contribute to economic growth.

ix. Cultural Relevance: Acknowledging the importance of preserving and promoting Nigeria’s rich cultural heritage within the education system, fostering a sense of identity, pride, and belonging among students.

x. Infrastructure Development: Investing in infrastructure such as schools, libraries, and laboratories to create conducive learning environments for students and teachers.

effective and engaging lessons using modern teaching methods and technologies.

vi.Partnerships and Collaboration: Collaborating with various stakeholders, including government agencies, private sector organizations, civil society, and international partners, to leverage resources, expertise, and best practices in education delivery and improvement.

vii. STEM Education: Promoting Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education to cultivate a workforce capable of driving innovation and technological advancement.

viii. Entrepreneurship Education: Introducing entrepreneurship education to foster an entrepreneurial mindset among students and empower them to create jobs and contribute to economic growth.

ix. Cultural Relevance: Acknowledging the importance of preserving and promoting Nigeria’s rich cultural heritage within the education system, fostering a sense of identity, pride, and belonging among students.

x. Infrastructure Development: Investing in infrastructure such as schools, libraries, and laboratories to create conducive learning environments for students and teachers.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: Implementing robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to assess the effectiveness of education policies, monitor student learning outcomes, measure the effectiveness of education programs, and inform evidence-based decision-making.

xii. Adaptability and Innovation: Building flexibility and adaptability into the education system to respond to changing needs and circumstances, fostering a culture of innovation and continuous improvement.

V.RECOMMENDATIONS: REFORM OF EDUCATION POLICY AND PRACTICE IN NIGERIA

- Recommended Philosophical Basis of Nigerian Education

The following philosophical foundations can provide guiding principles for shaping educational policies and practices in Nigeria to reform Nigerian education into the human capital generator it needs to be while reflecting the country’s diverse cultural, social, and historical contexts.

i. Human-centeredness and Intellectualism: Human-centered education focuses on the holistic development of the individual, emphasizing the development of the learner’s critical thinking, creativity, innovation prowess and all-round personal growth. In Nigeria, human-centered principles can guide educational practices that prioritize the well-being and intellectual empowerment of students, nurturing their full potential as individuals and members of society.

Intellectualism refers to engagement with, and respect for, seemingly abstract ideas and concepts as the essential foundation for progress in all spheres of human activity, including invention and innovation, systems of governance, and the success of national economies.

ii.Social Reconstructionism: This philosophy views education as a tool for addressing social inequalities and promoting social justice. In Nigeria, social reconstructionist principles will advocate for educational policies and practices that empower marginalized communities, challenge systemic injustices, and promote inclusive development.

iii. Nationalism and Cultural Identity: Given Nigeria’s diverse cultural landscape, educational philosophy often includes elements of nationalism and cultural identity. This involves promoting a sense of pride in Nigerian heritage, history, and traditions while also fostering unity and solidarity among the country’s diverse ethnic and cultural groups.

iv.Pragmatism: Pragmatic philosophy emphasizes practical experience, problem-solving, and experiential learning. In Nigerian education, a pragmatic approach can guide curriculum development and teaching methods that prioritize real-world relevance, vocational skills development, and entrepreneurship education

v.Educational Equity and Inclusion: Grounded in principles of fairness, justice, and equal opportunity, this philosophy emphasizes the importance of addressing disparities based on gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and disability. In Nigeria, educational equity and inclusion are essential principles for ensuring that all students have access to quality education and opportunities for success.

- Repositioning the Teaching Profession – Teacher Training and Teacher Pay

Efforts to reform teaching must focus on two interconnected areas:

Philosophical reorientation of the teaching profession

A philosophical reorientation of the teaching profession is imperative, moving away from the perception of teaching as a less desirable option, as outlined in the Ministerial Strategic Plan for Education (2018-2022). This shift requires a comprehensive reevaluation of the social, economic, and intellectual aspects of the teaching profession. Teaching should be recognized and esteemed as a vital profession responsible for fostering human capital development. Educators should be viewed as problem-solvers, facilitating value creation within the human capital ecosystem, and be trained accordingly. The government must demonstrate a commitment to enhancing the attractiveness of the profession by offering improved and timely remuneration packages, ensuring the provision of essential infrastructure, and more.

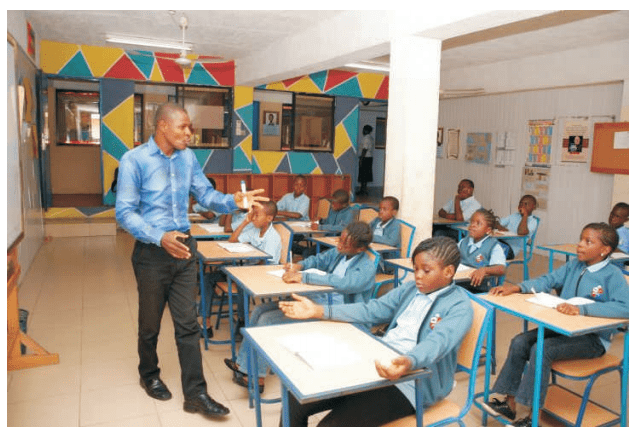

Additionally, there must be a societal shift in recognizing teaching as a respected and supported profession that attracts top talent. Finland and South Korea, for example, top the list of developed countries with the best education systems because these countries have a strong culture of education in which education is highly valued and teachers enjoy a high status in society.

Enhancement of teaching efficacy

To enhance teaching effectiveness, it is essential to broaden the opportunities for teacher training. Pre-service teacher training at National Colleges of Education and Institutes of Education within Universities should be revised to align with the evolving demands of the 21st century. Continuous professional development for educators at all levels is vital in a rapidly changing world. The teacher education curriculum must be redesigned to accommodate advancements in subject knowledge and to equip teachers with the ability to continuously enhance their teaching skills. Particularly in Nigeria, where societal challenges impact the quality of education, teachers should be trained as education solution providers, equipped with intellectual curiosity, professional insight, and critical thinking skills to address local educational challenges. Modern teachers should be seen as educational thought leaders with a profound understanding of their role within the economy. Concepts such as strategic thinking, design thinking, and social entrepreneurial leadership should be integrated into both pre-service and in-service teacher training programs. The establishment of Teacher Resource Centers, as proposed by the Revised National Policy on Education (2013), should be expanded to meet existing needs. Emphasizing education research is crucial, as sustainable reforms in the education sector must be informed by ongoing empirical and qualitative insights to evaluate the effectiveness of reform practices.

- Financial Investment in Education

The education sector urgently requires enhanced financing, accompanied by clear and impartial guidelines for education financing that transcend individual political interests. Over the course of the past four years, Oyo State, for example, has demonstrated a commendable commitment to increasing the allocation of funds towards education. This serves as a noteworthy model that should be emulated by various levels of government to prioritize the advancement of education. It is imperative to address the issue of excessive costs of governance within annual budgets to enable the efficient utilization of limited resources towards essential socioeconomic priorities such as education. Moreover, there is a pressing need to diversify the sources of funding for education beyond government resources by incorporating greater private sector investment. Recent data indicates a notable growth in diaspora remittances and alumni financial contributions to educational institutions, highlighting a promising trend towards increased involvement of the diaspora community and alumni in the financing of education.

One notable example is the takeover of the famous Government College Umuahia, which fell into decay after the 1980s, from the Abia State Government by the school’s alumni, and the reinvention of the school under the non-profit Fisher Educational Development Trust as its new owner. A massive rebuilding and refurbishment of the institution followed, with approximately N3 billion in

funds donated by its Old Boys. The institution, which first had to be closed in order to reposition it, has now been reopened as a modern, 21st century secondary school under private and non-profit ownership. This Guest Lecturer happens to be an Old Boy of this institution and contributed his widow’s mite to the school’s restoration. Several other secondary schools in Nigeria are undertaking similar efforts at revival under alumni initiatives. There is a need and space for the active engagement of alumni, including those in the diaspora, in providing structured and systematic financial support for education initiatives.

Foreign investment in education in Nigeria should be encouraged and strategically pursued. This approach will serve three functions – enhance the pool of human capital needed for broad-based economic productivity, limit the drain on Nigeria’s foreign reserves created by the demands of paying for tertiary education abroad, and reverse the brain drain. An example Nigeria can look at is the EduCity Iskandar in Malaysia, a multi-campus education city with 305 acres of universities, higher education institutions, research and development centers that has Malaysian campuses of foreign universities such as Newcastle University, Maastricht University, and University of Reading. Another example is Rwanda, which hosts a campus of the prestigious Carnegie Mellon University headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in the United States Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in the United States.

- Tackling Access to and Quality of Foundational Learning (Lessons from Burundi)

The World Bank blog, 2024 reported that the Government of Burundi made strides in the quality of foundational learning by investing in high-quality instruction in children’s mother tongue, Kirundi, in early grades. There has also been a commitment to building teams of qualified and dedicated teachers and to nurturing community engagement and support. The results of these initiatives are underscored by the ‘Programme d’analyse des systèmes éducatifs de la CONFEMEN’ (PASEC) student assessment, which shows that Burundian children shine in reading and mathematics, particularly in early grades, outperforming their peers in other Sub-Saharan African Francophone countries. The World Bank-funded Burundi Early Grade Learning Project (PAADESCO) has played a pivotal role in maintaining the quality of education by bolstering the primary school curriculum, enhancing teaching, and learning resources, extending school feeding programs, and providing essential school kits. Building on the successes of PAADESCO, the Human Capital Development Project, currently under preparation, aims to further advance reforms of the curriculum. It will concentrate on facilitating a smooth transition from Kirundi to French as the language of instruction, helping ensure uninterrupted learning.

To effectively tackle the issue of the access-quality conundrum within Nigeria’s education system and emphasize the importance of investment in primary and secondary education, the subsequent recommendations can be derived from the model set forth by Burundi, which includes the need for infrastructure improvement, curriculum review and development, teacher recruitment and training, ensuring equity of access, and appropriate community/stakeholder engagement. The nature of education expenditure also matters greatly. Most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa spend 10 times more on university students than on primary school pupils, according to UNESCO. Burundi offers an interesting example. The country brought down its numbers of out of school children from 723,000 in 1999 to 10,000 in 2009, increasing its investment in education from 3.2% to 8.3%. Burundi dedicated a much larger portion of its education budget to primary education than secondary schools and universities. By adopting these recommendations and learning from the experiences of countries like Burundi, Nigeria can make significant strides in addressing the access-quality conundrum in primary and secondary education. Investing in these foundational levels of education is essential for building a skilled workforce, promoting social mobility, and driving sustainable development and prosperity across the nation.

- Curriculum Reform

Given the rapidly evolving global landscape and the increasing importance of technology, science, entrepreneurship, and teacher training in driving economic growth and innovation, Nigeria must realign its education curriculum, particularly at the tertiary level, to prioritize these areas. By allocating 70% of the curriculum to technology, science, entrepreneurship, and teacher training, Nigeria can better equip its youth with the skills and knowledge needed to compete in the 21st-century economy, foster entrepreneurship, and improve the quality of education across the board. I also recommend that Ethics becomes a compulsory subject in the education curriculum in Nigeria at both primary (in a simplified and elementary form) and secondary school in a more comprehensive form. This will help achieve the educational objective of creating good and responsible citizens.

- Pedagogy Reform

There is also a need to shift the pedagogical practices of the Nigerian classroom from one that emphasizes rote memorization to more intellectual engagement, creative thinking, and experiential learning. For instance, in tertiary education, it is imperative to foster the connection between academia and industry to improve the socio-economic impact of education. Tertiary students require exposure to real-world challenges that their education is designed to help them address. Edem Ossai (2023) put forth two models to assist students in applying abstract concepts learned in the classroom to practical situations. The first model suggests the establishment of discipline-based incubation spaces. In STEM fields, these spaces can function as Innovation Centers where students use STEM principles to tackle local issues. For non-STEM disciplines like arts, social sciences, and law, these incubation spaces can serve as Thinking Clinics where students engage with real-life case studies that necessitate the application of their knowledge.

The second model recommends the implementation of Experiential Capstone Projects to replace the current theoretical undergraduate thesis model. These projects would require students to develop solutions to community problems, marking the culmination of their academic journey. These models draw on existing practices in higher education and have been successfully implemented by universities in Africa, notably the African Leadership University in Rwanda. This successful implementation showcases the feasibility of such approaches even within the intricate African educational landscape.

Enhancing pedagogy reform in primary and secondary schools involves investing in comprehensive teacher training programs to equip educators with modern pedagogical techniques, subject matter expertise, and effective classroom management skills. Provide ongoing professional development opportunities to keep teachers updated on best practices and innovative teaching methods. It is also imperative to integrate technology into the classroom to enhance teaching and learning experiences and to provide teachers with access to educational resources, interactive multimedia tools, and online platforms for collaborative learning. Instruction strategies should also be catered to student’s learning systems and should accommodate diverse student needs. The classroom environment should encourage active participation, inquiry-based learning, and critical reflection while also fostering student engagement through cooperative learning structures, Socratic questioning techniques, and experiential activities. By implementing these strategies, primary and secondary schools can experience pedagogical reform, improve teaching and learning outcomes, and create a conducive environment for student success and academic excellence.

Finally, by investing in the practices and tools that foster creative thinking and innovation, Nigeria can create a more dynamic and resilient education system that meets the needs of students and the labor market, ultimately driving sustainable growth and prosperity for the nation.

- Standards and Compliance

Nigerian education policy revitalization should also prioritize building and implementing effective standards and regulatory measures that ensure the compliance of all forms of education institutions to the necessary quality of the educational system. Some of the paramount forms of standards necessary are:

i.Curriculum Standards: Establishing a framework for curriculum development that emphasizes relevance, flexibility, and alignment with national development goals. There’s a need for a broad-based curriculum that integrates academic, vocational, technical, and entrepreneurial skills.

ii.Assessment Standards: Developing guidelines to monitor student’s progress through continuous assessment and evaluation and ensure learning outcomes are achieved. It encourages the use of various assessment methods, including formative and summative assessments, to provide a comprehensive picture of student achievement.

iii. Teacher Certification and Qualification Standards: Setting requirements for teacher education and professional development in ensuring quality teaching. It emphasizes the need for qualified and well-trained teachers and outlines requirements for teacher certification and licensure.

iv.Accreditation Standards: Accreditation by recognized bodies such as the National Universities Commission (NUC) and the National Board for Technical Education (NBTE) is a means to ensure quality assurance and improvement in educational institutions.

v.Accessibility and Inclusion Standards: This emphasizes the importance of providing equal access to education for all Nigerian citizens, regardless of gender, ethnicity, religion, or socio-economic status. It calls for measures to promote inclusive education and address barriers to learning, including those faced by marginalized and vulnerable groups.

V.CONCLUSION

Nigeria is urgently in need of educational policy that can enhance its human capital, make it globally competitive, and bolster its standing within the global community. This kind of education must prioritize access and quality by emphasizing literacy, skills, and national values. Our country has suffered a massive, progressive collapse of values over the past several decades. This has happened largely because we have taken our eyes off the ball of education, which is the foundation upon which every society rises or falls. The progressive loss of respect for ideas and education as a value naturally extended to a loss of priority for education as a national priority as the national focus shifted to the effects of Nigeria’s resource curse from the oil boom – easy money and illicit wealth from rent-seeking activities. The domino effect of this decline in values was felt in the death of a drive for access to education and the quality of education. As the private sector became increasingly involved in education through the establishment of both elite and pseudo-elite private schools, Nigeria’s public education system increasingly faced a struggle for survival and relevance.

We have not lacked education policy in Nigeria. Implementation, however, has always been our big weakness. But even the policies we have are out of date and out of place if we seek to transform Nigeria to become a nation, not just a country, to become a global power and not just a “potential” power. We can do it. Just look at how our compatriots thrive in foreign lands where the right philosophies drive education, making it a true national priority in terms of purpose, strategy, and investment.

We must return to education as a national priority, and to education that has a clear objective and purpose. There is no alternative but to reform our public education system and make it world class.

No country in the world has risen with a reliance on private sector educational institutions alone. The reason is obvious: private education is expensive, and only a tiny percentage of citizens can afford it. Education is a fundamental human right. If that right is to be respected, then education must be a national public good – accessible, qualitative, and affordable. This is the path to Nigeria’s rise in the 21st century.

References

Emily Markovich Morris and Ghulan Omar Qargha (2023), “In the Quest to Transform Education, Putting Purpose at the Center is Key”, Brookings Institution Commentary, www.brookings.edu/articles

Ezeyi, V.N., Ene, N.N.S., & Nwosu, R.Y. (2013). National Policy on Education in Nigeria [Article]. In: Historiological Dimensions of Nigerian Education. Equity Ventures in Conjunction with Mega Atlas Projects Limited, pp. 91-150. ISBN 978-978-49195-0-4.

OECD (2022), Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en.

Ossai, Edem (2023, September 20) Redefining the Role of Tertiary Educator in Nigeria [Webinar]. The Education Partnership Webinar Series.

Euiryeong Jeong (2020). Education Reform for the Future: A Case Study of Korea. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT). Vol. 16, Issue 3 (Special Issue), pp. 66-81